27 Sept 2020

Harz Tours - Collection

2020

I had planned a spring journey to Lithuania and Latvia that fell victim to Corona, though I hope I can do it some other time. But with traveling within Germany being rather safe now, I decided to sneak in a little autumn tour and went to one of my favourite destinations for a few days – visiting Goslar and Quedlinburg in the Harz, including some hiking. I've visited both towns before, but during day trips that didn't leave me as much time – this time I got a lot of photos, so I'll be able to write virtual town tours that got some real illustrations. For now, let's have a brief look in the style of my Travel Booty posts.Goslar, seen from the Rammelsberg mountain

The Harz mountain range is rich in silver and ore and thus has been cultivated since the Bronze Age. Mining became important in the Middle Ages, settlements developed in the valleys, cattle was sent grazing on the slopes and trees were used – and later replanted – for building, mining and firewood. The Harz today is a cultural landscape, but with parts that remain but little altered, or are allowed to reset to their natural state; those now encompass the Harz National Park.Goslar, the palatine castle

Let's start with a well known building that more or less represents Goslar: The iconic palatine castle is a 19th century reconstruction based on the remains of the 11th century building, one of the main seats of the Salian emperors. They traveled around in their realm, but the main feasts like Easter, Christmas and such were usually celebrated in prominent palatine castles. The buildings had undergone various uses after the palace was no longer needed as royal seat after 1252, and was somewhat worse for the wear.Goslar, the market square

That photo of the market square was taken out of the window of my hotel room. In some places in the Harz, local slate shingles are not only used for roofing, but to protect the walls against the harsh climate as well.

The burghers of Goslar benefitted from the rich silver mines in the Rammelsberg mountain, and the town thrived, as the fine houses in the square demonstrate. It became a free Imperial city in 1290 and later joined the Hanseatic League. Goslar lost its independence only in the 16th century. Goslar, old houses at the Abzucht brook

Goslar declined in the 18th century, several fires destroyed parts the town. But enough of the Mediaeval and Early Modern buildings remained, and the increasing interest of the Hohenzollern emperors in old architecture led to a restoration boom in the mid- to late 19th century. Today, the old town and palatine castle hold UNESCO World Heritage status.Goslar, more pretty half timbered houses

The Rammelsberg has not only offered an important silver mine for centuries (mining has been discontinued only in 1988 because it became unprofitable), but also some nice hiking trails that offer views towards Goslar in the parts were the forest opens up to hillside grazings.The Maltermeister Tower

The Maltermeister Tower on the Rammelsberg was built some time before 1548 to protect the mines. It was also used as belfry for a bell to warn the miners and the town of approaching danger and to signal the begin of a shift. It was the quarter of the Maltermeister, the administrator of the wood used for the mines; that wood was measured in bushels, German Malter.The Herzberg Pond

On my way back, I passed the Herzberg Pond, a lovely spot of sparkling water among verdant hills. The pond is not natural, but considerably old; it was created as part of the Upper Harz Water Regale (Oberharzer Wasserregal) in 1561 by an earth and grass dam. It has been used as woodland swimming pool since 1926, after the mining technology no longer needed the water wheels. Pity I didn't bring s swimsuit; the water looked really cool and inviting.Hiking trail on the Rammelsberg

The Upper Harz Water Regale is a system of resevoirs, dams and ditches that dates back to the Middle Ages. Water was needed to drive the water wheels in the mines which pumped up the groundwater in the deeper mines – fighting water with water. The Harz water regale is one of the largest mining water systems in the world. It is a cultural monument since 1978. Today, the ponds and reservoirs are used for reecreational purposes.Quedlinburg, view to the chapter church and the palace

Another view from my hotel room, this time in Quedlinburg. The scaffolding on the cathedral has wandered a bit – last time I was there it covered the towers – but it is still the same one; repairs will continue until 2025 or so, I was told. Well, two visits still provided me with some photos of the parts not scaffolded in and closed to the public.Quedlinburg, view from the palace garden to the old town

Quedlinburg, another town listed as UNESCO World Heritage, is first mentioned in a charte by Heinrich I (the Fowler) dating from 922, as location of one of the many palatine castles spread across Germany during the Middle Ages and often used during the Easter celebrations. Heinrich I and several of his successors were entombed in Quedlinburg.Quedlinburg, old houses with the chapter church and palace in the background

Heinrich's widow Queen Mathilde obtained a grant from her son, Otto I, to establish a canoness chapter which she led for 30 years. In 994, Otto III granted the chapter the right of market, mint and tolls and thus laid the foundation for the development of the town. The town experienced an economical rise in the following centuries and gained more independence from the abbess of the chapter, the nominal lady of the town. In 1426, Quedlinburg joined the Hanseatic League.Quedlinburg, the town hall

During that time, the burghers began to build those beautiful half timbered houses some of which have survived and been restored. The representative town hall was built in 1310; in 1616 a Renaissance portal was added, and there are later changes from the 19th century that affect mostly the interior.Quedlinburg, Finkenherd Square

Luckily, the value of the historical substance of Quedlinburg's old town was reocgnised during GDR time (too often, old houses were dismantled and replaced with modern buildings instead) and specialists from Poland were called in to restore the half-timbered buildings. Quedlinburg became an East German show piece for state visitors.St.Wiperti, the crypt

St.Wiperti is a fine example of the Romanesque style. Heinrich I had the church erected on the foundations of an even older one. The exact relationship between the chapter church on the castle hill and St.Wiperti are still discussed; obviously the Ottonian and Salian emperors used both during their sojourns in Quedlinburg. But while the chapter church was occupied by ladies, St.Wiperti was a Premonsterian monastery for a time, and might also have been used by the royal clerical staff.Hiking trail in the Bode Valley

Since the Bode Valley is not far from Quedlinburg, I took the chance to have another hike in one of my favourite landscapes. I've bloogged about the valley here. This time I went further up the slope and walked to the Bodekessel, a little waterfall that washed out a cave in the cliffs (though the view down is so overgrown with shrubs that I could not catch a decent photo). The way consists of stones and small boulders, which makes hiking along that path 'interesting'. The Bodekessel

I had some time left upon return to Thale, so I decided to take the cabin lift to the Witches' Dance Floor, one of the many cliff tops surrounding the valley. Well, I'm not good with heights to begin with and didn't count on the wind that made the tiny cabin sway like a drunken sailor, but I survived. Better than a broomstick, anyway. The way down was less stressful and I could enjoy the view of the valley beneath a bit more.View from the Witches' Dance Floor

The Hexentanzplatz is a granite plateau overlooking the Bode Valley and several other cliffs. The site has been a popular tourist spot since the late 19th century (with a theatre, a zoo, an overpriced restaurant etc.), though it had been in use before, for example as a pagan cult site prior to the Christianisation of the Saxon tribes. At at this time of the year and with the Chinese tourist groups missing, it wasn't so crowded. The view was definitely worth the visit (and ride in the cabin lift).Bode river

2014

My father and I undertook another tour to explore more of the eastern Harz mountains and the lands around. Historically, this is the area where the Ottonian and Salian emperors had some of their ancestral lands, and spent a lot of time. Hiking around we came up with more fun than just old churches, though.

Moated castle Westerburg

The Westernburg is the oldest moated castle in Germany that is still intact. It is first mentioned as fief of the Counts of Regenstein in 1180. When the family died out, the castle changed possession several times until it came into the hands of the administration in Halberstadt. Today it houses a spa hotel, but is still accessible for visitors, and they serve some good ice cream. *grin*

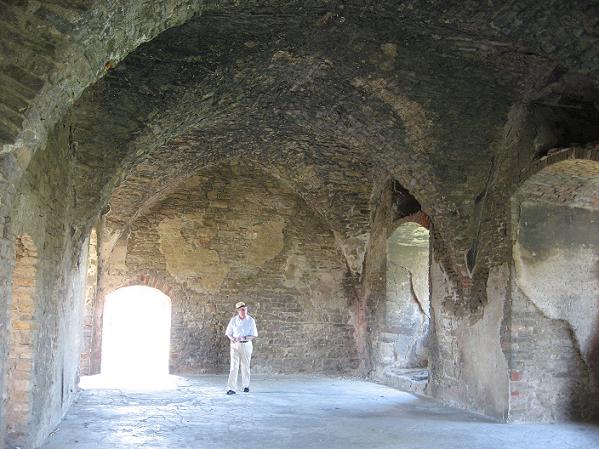

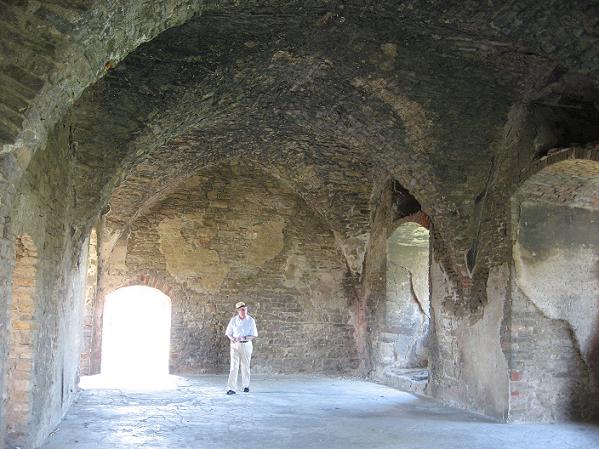

Westerburg, inside view

The ringwall with two water filled trenches encloses an areal of 350x300 metres; the castle itself is 60x80 metres, with the houses built directly to the two metres thick curtain wall, and a round keep in the western part. Later, a square shaped set of buildings was added to the west; used as living quarters since the Renaissance.

Castle Lauenburg, the inner gate (with an Ent at work *wink*)

Much less is left of the Lauenburg, another of our typical hilltop castles. Castle Lauenburg was built by Heinrich IV in 1164 as part of a chain of Harz castles which also included the Harzburg. One of its functions was the protection of the town of Quedlinburg (where I've been a few years ago). Friedrich Barbarossa conquered the castle during his war against Heinrich the Lion (1180); it was destroyed already in the 14th century.

Lauenburg, keep of the outer bailey

The entire complex was once 350 metres long (that's coming close to some Norman whoppers like Chepstow), covering the Ramberg hilltop. The castle is divided in an outer bailey (Vorbug) sitting on its own peak with a still somewhat intact keep, and the main castle on the promontory, both separated by a natural trench and additional walls. The 140 metres long main castle was again separated into three baileys with two keeps.

Stolberg / Harz

Stolberg is a small town in the Harz where my father spent some holidays as child. It's always nice coming back to it after the debris left behind by years of GDR mismanagement has been turned into beautiful houses again. The town started as settlement connected to mining in the Harz mountains in AD 1000, and was in possession of the Counts of Stolberg since the 12th century. The Stolberg family held the castle (nowadays a Renaissance building on a hill above the town) until 1945.

Wernigerode / Harz, the town hall

Wernigerode is one of those towns full of pretty half timbered houses, and the town hall is particularly beautiful. The origins of the town cannot be traced before it appears in documents in 1121, when the then-to-be-called Counts of Wernigerode took their seat there. The place got town rights in 1229. After the Wernigerode line died out in 1429, the town came into possession of the Counts of Stolberg until 1714 when it became part of Preussen.

The cathedral in Halberstadt

The cathedral in Halberstadt is a predominately Gothic building that replaced an older church which was destroyed during Heinrich the Lion's wars with Friedrich Barbarossa. The main nave dates to 1260 and is influenced by the French style, but shortage of money led to delays, so the cathedral was finished only in the 14th century with the old Romanesque quire still in use until 1350 when it was replaced with a Gothic one. The transepts were added in 1491. Some things never change. ;-)

Halberstadt, Church of Our Lady, main nave

The Church of Our Lady in Halberstadt is a fine example of a four towered Romanesque church, dating back to 1005 albeit with changes in the 12th century (addition of the side naves), and again in the 14th century (cross grain vaulted ceiling to replace the former timber one). Even younger alterations during the 19th century historicism (wannabe Middle Ages style) have partly been deconstructed in the renovations post-WW2.

Benedictine monastery Huysburg

Huysburg Monastery was founded in 1080 as Benedictine monastery by Bishop Burchard of Halberstadt. It fell to the secularization in 1804, but became a monastery again in 1972; the only Benedictine monastery in the GDR. The church is a Romanesque basilica (unfortunately with Baroque bling inside). Other buildings have been added over the centuries; some of them serve as guest houses and meeting rooms today.

A Brigands' Lair - the Daneil Cave in the Huy Mountain

This cave can be found in the Huy mountain, a sandstone ridge now grown with beeches. There is a legend about an abducted maiden who was forced to work for a gang of evil robbers until she managed to escape, alert the village and give the guys their just dessert. The place has been lived in, maybe even by some unsavoury guys, but there are no documents about a veritable brigand gang harrassing the surroundings for years.

The cave houses in Langenstein

Here we got some 19th century Hobbit dwellings. *grin* They can be found in several places in the village of Langenstein. Some of these go back to the 12th century and were successively expanded. The last inhabitant left his cave in 1916. They were actually up to the living standard of the time, cool in summer and warm enough in winter thanks to ovens. The toilets were outside in the (in)famous plank huts.

One of the houses, interior (the kitchen; important in a hobbit hole)

The caves are of varying size; the average is 30 square metres for a family, with a kitchen and larder, a living room, and sleeping quarters. The caves were not poor man's hovels, but respectable housings for the working class. Several of them have been lovingly restored and equipped with old-fashioned furniture.

A very crazy way through sandstone cliffs

This crazy way leads through the red sandstone and musselkalk of the Huy mountain up to the remains of a castle. There are caves here, too, those dating back to the time of the Germanic tribes living here in pre-Roman times. They have been used until the 20th century, but they are larger and less comfortable, with no separate rooms. The last people to live there were some refugees from WW2 (until better places could be found for them).

Remains of Castle Langenstein (pretty much all there is)

At the end of the crazy way are some bits of castle wall. Castle Langenstein was built by the bishop of Halberstadt in the 12th century and once was a large and imposing structure covering the entire plateau of the hill. It was destroyed during the thirty Years War and used as quarry afterwards. Today only a section of a wall with the window opening is left. But the view over the land all the way to Halberstadt is nice.

Outline of a prehistoric longhouse

These are the outlines of a longhouse from the early Bronze Age (2300 - 1800 BC) near Benzingerode. When the new interstate was built, lots of prehistoric finds came up that are now spread to several museums. The area is not so far from the place where the famous Nebra disc has been found - quite a busy place some 4000 years ago. There are several menhirs in the surrounding fields, but no longer accessible. Since people kept stomping over the fields with no regard for the corn, the farmers fenced them in.

A glacier mill in the Huy Mountain

This bit of geological fun can be found in the Huy mountain ridge. Glacier mills are the result of cracks in the ground where glaciers slowly pushed forward. Melting water and small debris would run down those cracks and over time, carve canons, where the small stones washed out kettle shaped holes, the glacier mills. The mills in the Huy date back to the Saalian stage of the Ice Ages (352,000 - 130,000 years ago) and are the only ones to be found in Germany outside the Alps.

A river in the Harz

A typical Harz river, clear and cold, running over boulders.

2008

Our journey to the Harz and Quedlinburg was fun, but also very hot with about 32°C during the day and lots of sunshine. Fortunately, the nights were a bit cooler since the temperature in the Harz drops somewhat more than in Göttingen (which can be a steaming soup bowl in summer) and the hotel was situated at a little river that brought a cool breeze in the evenings.

Regenstein Castle

There were several beers with my name on them every evening, and they just evaporated somehow. I don't even want to begin and try to figure out how many litres of water I drank; it must have been a small lake. Ice cream is a good thing on hot days, too, especially iced coffee with vanilla ice cream and dab of whipped cream on top.

One of the caves in the Regenstein

But it was definitely fun, including the climbing of some rocks in sandals. I'm the proverbial German when it comes to wearing shoes unsuitable for mountains. Maybe I should volunteer as test person for sandals - if they survive the ways I walk, they will survive about anything.

Falkenstein Castle

The Harz was always a politically important area throughout history, not at least because it's rich in ore, and so Mediaeval times saw a lot of castles on the tops of those hills and mountains. Many of the about 500 Harz castles have left nothing more behind than some tumbled stones and traces in the ground that point to an ancient trench or earthen wall, but some are still formidable ruins or even reconstructed to mirror their former beauty.

View from Falkenstein Castle to the Selke valley

Germany can be very green, too.

Arnstein Castle, remains of the keep and great hall

Many German castles are less grand than the Norman castles because space on summits is more limited, but their owners and the architects sometimes got very inventive when it came to making the land - or rather, the bedrock - part of the castle construction. The Regenstein with its part natural, part artificial caves surrounding the keep is a fine example.

Arnstein, great hall

Not all castles were in the focus of the great history the way the Harzburg (which I hope to see in August) was, but they all have their stories. And legends. The Harz is rich in legends, and you'll learn some in the time to come.

View to the north-eastern Harz foothills

I've got some Romanesque churches for you as well. There is a road - or rather, a number of connected roads all over Germany - leading to the most interesting Romanesque buildings. You can visit churches and a few castles and other buildings all the way from the Alpes to the Baltic Sea coast, following the Strasse der Romanik.

Quedlinburg Cathedral, main nave

I got only inside views of this one because the towers were wrapped in scaffolding, and since the catherdral sits on a hill, surrounded by other buildings, the towers are pretty much the only thing you can see. The inside has been renovated already and looks a lot better than last time I was there, but unfortunately, the crypt is still closed.

Chapter Church Gernrode, south side

This one is really beautiful and in good condition. Nice and cool inside as well. *grin* Churches are a good place to visit on a hot day.

Both Quedlingburg and Gernrode were Canoness Chapters for noble ladies who would live more or less like nuns only without taking permanent vows. That way they could leave and marry if family politics changed. But some stayed all their life and the Abbesses, esp. the ones of Quedlinburg, held a lot of power.

Konradsburg Monastery, crypt

Not much remains of the Konradsburg Monastery, only the choir of the church and the crypt which is undergoing restoration (almost finished, so I got some good photos). But the history behind it is interesting; Konradsburg is the only monastery that started off as castle (Burg = castle, you've seen that word in several names).

Michaelstein Monastery, cloister

Remains of a 12th century Cisterciensian monastery. The cloister and some of the outhouses have been preserved and today house a museum for music instruments, a school, and a restaurant.

Michaelstein Monastery, herbal garden

I want a garden like that.

Bode River

One of the many shots I took of that one. I love running water.

Views

Of course, I used the high vantage points on the mountain peaks of the Harzburg and the Ilsestein to take some photos, and despite the somewhat hazy atmosphere of early autumn, a number of them turned out fine.

View from the Harzburg towards the Brocken - the mist-veiled mountain in the background - in the morning sun. The Brocken (1142 m) is the highest mountain in the Harz and the central meeting place of German witches on Walpurgis Night. The place is a bit too touristy for my taste so I haven't been to the top yet. During the time of the German division the Brocken was Russian military zone and not accessible from either West or East.

Another view from the Harzburg. Fall has arrived in the Harz already, with crisp mornings, mists rising from the vales, the first brown leaves dancing in the breeze, and a lower sun tinting the trees golden like a last greeting of summer. A farewell.

On the other side of the Harzburg, the view goes towards the Norddeutsche Tiefebne, a mostly flat area that stretches all the way from the Harz to the Baltic Sea. In the distance, though beyond view, lies Braunschweig, the main seat of Heinrich the Lion; and further to the north-east Magdeburg and Berlin. The town at the foot of the mountain is Bad Harzburg, a popular spa town.

This one is less spectacular but pretty. The stones to the right are not a natural formation this time, but the remains of a curtain wall. The photo was taken at Stapelburg Castle, one of the smaller fortresses in the Harz. I got a few pics of what is left of the main hall and the trenches, so I'll leave a more detailed description to another post.

Another view from the Paternoster cliffs on the Ilsestein mountain. The blueish shadow to the left is the Brocken again - you can't miss that big boy from most of the Harz's high vantage points. The entire area is a National Park today.

2020

I had planned a spring journey to Lithuania and Latvia that fell victim to Corona, though I hope I can do it some other time. But with traveling within Germany being rather safe now, I decided to sneak in a little autumn tour and went to one of my favourite destinations for a few days – visiting Goslar and Quedlinburg in the Harz, including some hiking. I've visited both towns before, but during day trips that didn't leave me as much time – this time I got a lot of photos, so I'll be able to write virtual town tours that got some real illustrations. For now, let's have a brief look in the style of my Travel Booty posts.

The Harz mountain range is rich in silver and ore and thus has been cultivated since the Bronze Age. Mining became important in the Middle Ages, settlements developed in the valleys, cattle was sent grazing on the slopes and trees were used – and later replanted – for building, mining and firewood. The Harz today is a cultural landscape, but with parts that remain but little altered, or are allowed to reset to their natural state; those now encompass the Harz National Park.

Let's start with a well known building that more or less represents Goslar: The iconic palatine castle is a 19th century reconstruction based on the remains of the 11th century building, one of the main seats of the Salian emperors. They traveled around in their realm, but the main feasts like Easter, Christmas and such were usually celebrated in prominent palatine castles. The buildings had undergone various uses after the palace was no longer needed as royal seat after 1252, and was somewhat worse for the wear.

That photo of the market square was taken out of the window of my hotel room. In some places in the Harz, local slate shingles are not only used for roofing, but to protect the walls against the harsh climate as well.

The burghers of Goslar benefitted from the rich silver mines in the Rammelsberg mountain, and the town thrived, as the fine houses in the square demonstrate. It became a free Imperial city in 1290 and later joined the Hanseatic League. Goslar lost its independence only in the 16th century.

Goslar declined in the 18th century, several fires destroyed parts the town. But enough of the Mediaeval and Early Modern buildings remained, and the increasing interest of the Hohenzollern emperors in old architecture led to a restoration boom in the mid- to late 19th century. Today, the old town and palatine castle hold UNESCO World Heritage status.

The Rammelsberg has not only offered an important silver mine for centuries (mining has been discontinued only in 1988 because it became unprofitable), but also some nice hiking trails that offer views towards Goslar in the parts were the forest opens up to hillside grazings.

The Maltermeister Tower on the Rammelsberg was built some time before 1548 to protect the mines. It was also used as belfry for a bell to warn the miners and the town of approaching danger and to signal the begin of a shift. It was the quarter of the Maltermeister, the administrator of the wood used for the mines; that wood was measured in bushels, German Malter.

On my way back, I passed the Herzberg Pond, a lovely spot of sparkling water among verdant hills. The pond is not natural, but considerably old; it was created as part of the Upper Harz Water Regale (Oberharzer Wasserregal) in 1561 by an earth and grass dam. It has been used as woodland swimming pool since 1926, after the mining technology no longer needed the water wheels. Pity I didn't bring s swimsuit; the water looked really cool and inviting.

The Upper Harz Water Regale is a system of resevoirs, dams and ditches that dates back to the Middle Ages. Water was needed to drive the water wheels in the mines which pumped up the groundwater in the deeper mines – fighting water with water. The Harz water regale is one of the largest mining water systems in the world. It is a cultural monument since 1978. Today, the ponds and reservoirs are used for reecreational purposes.

Another view from my hotel room, this time in Quedlinburg. The scaffolding on the cathedral has wandered a bit – last time I was there it covered the towers – but it is still the same one; repairs will continue until 2025 or so, I was told. Well, two visits still provided me with some photos of the parts not scaffolded in and closed to the public.

Quedlinburg, another town listed as UNESCO World Heritage, is first mentioned in a charte by Heinrich I (the Fowler) dating from 922, as location of one of the many palatine castles spread across Germany during the Middle Ages and often used during the Easter celebrations. Heinrich I and several of his successors were entombed in Quedlinburg.

Heinrich's widow Queen Mathilde obtained a grant from her son, Otto I, to establish a canoness chapter which she led for 30 years. In 994, Otto III granted the chapter the right of market, mint and tolls and thus laid the foundation for the development of the town. The town experienced an economical rise in the following centuries and gained more independence from the abbess of the chapter, the nominal lady of the town. In 1426, Quedlinburg joined the Hanseatic League.

During that time, the burghers began to build those beautiful half timbered houses some of which have survived and been restored. The representative town hall was built in 1310; in 1616 a Renaissance portal was added, and there are later changes from the 19th century that affect mostly the interior.

Luckily, the value of the historical substance of Quedlinburg's old town was reocgnised during GDR time (too often, old houses were dismantled and replaced with modern buildings instead) and specialists from Poland were called in to restore the half-timbered buildings. Quedlinburg became an East German show piece for state visitors.

St.Wiperti is a fine example of the Romanesque style. Heinrich I had the church erected on the foundations of an even older one. The exact relationship between the chapter church on the castle hill and St.Wiperti are still discussed; obviously the Ottonian and Salian emperors used both during their sojourns in Quedlinburg. But while the chapter church was occupied by ladies, St.Wiperti was a Premonsterian monastery for a time, and might also have been used by the royal clerical staff.

Since the Bode Valley is not far from Quedlinburg, I took the chance to have another hike in one of my favourite landscapes. I've bloogged about the valley here. This time I went further up the slope and walked to the Bodekessel, a little waterfall that washed out a cave in the cliffs (though the view down is so overgrown with shrubs that I could not catch a decent photo). The way consists of stones and small boulders, which makes hiking along that path 'interesting'.

I had some time left upon return to Thale, so I decided to take the cabin lift to the Witches' Dance Floor, one of the many cliff tops surrounding the valley. Well, I'm not good with heights to begin with and didn't count on the wind that made the tiny cabin sway like a drunken sailor, but I survived. Better than a broomstick, anyway. The way down was less stressful and I could enjoy the view of the valley beneath a bit more.

The Hexentanzplatz is a granite plateau overlooking the Bode Valley and several other cliffs. The site has been a popular tourist spot since the late 19th century (with a theatre, a zoo, an overpriced restaurant etc.), though it had been in use before, for example as a pagan cult site prior to the Christianisation of the Saxon tribes. At at this time of the year and with the Chinese tourist groups missing, it wasn't so crowded. The view was definitely worth the visit (and ride in the cabin lift).

2014

My father and I undertook another tour to explore more of the eastern Harz mountains and the lands around. Historically, this is the area where the Ottonian and Salian emperors had some of their ancestral lands, and spent a lot of time. Hiking around we came up with more fun than just old churches, though.

The Westernburg is the oldest moated castle in Germany that is still intact. It is first mentioned as fief of the Counts of Regenstein in 1180. When the family died out, the castle changed possession several times until it came into the hands of the administration in Halberstadt. Today it houses a spa hotel, but is still accessible for visitors, and they serve some good ice cream. *grin*

The ringwall with two water filled trenches encloses an areal of 350x300 metres; the castle itself is 60x80 metres, with the houses built directly to the two metres thick curtain wall, and a round keep in the western part. Later, a square shaped set of buildings was added to the west; used as living quarters since the Renaissance.

Much less is left of the Lauenburg, another of our typical hilltop castles. Castle Lauenburg was built by Heinrich IV in 1164 as part of a chain of Harz castles which also included the Harzburg. One of its functions was the protection of the town of Quedlinburg (where I've been a few years ago). Friedrich Barbarossa conquered the castle during his war against Heinrich the Lion (1180); it was destroyed already in the 14th century.

The entire complex was once 350 metres long (that's coming close to some Norman whoppers like Chepstow), covering the Ramberg hilltop. The castle is divided in an outer bailey (Vorbug) sitting on its own peak with a still somewhat intact keep, and the main castle on the promontory, both separated by a natural trench and additional walls. The 140 metres long main castle was again separated into three baileys with two keeps.

Stolberg is a small town in the Harz where my father spent some holidays as child. It's always nice coming back to it after the debris left behind by years of GDR mismanagement has been turned into beautiful houses again. The town started as settlement connected to mining in the Harz mountains in AD 1000, and was in possession of the Counts of Stolberg since the 12th century. The Stolberg family held the castle (nowadays a Renaissance building on a hill above the town) until 1945.

Wernigerode is one of those towns full of pretty half timbered houses, and the town hall is particularly beautiful. The origins of the town cannot be traced before it appears in documents in 1121, when the then-to-be-called Counts of Wernigerode took their seat there. The place got town rights in 1229. After the Wernigerode line died out in 1429, the town came into possession of the Counts of Stolberg until 1714 when it became part of Preussen.

The cathedral in Halberstadt is a predominately Gothic building that replaced an older church which was destroyed during Heinrich the Lion's wars with Friedrich Barbarossa. The main nave dates to 1260 and is influenced by the French style, but shortage of money led to delays, so the cathedral was finished only in the 14th century with the old Romanesque quire still in use until 1350 when it was replaced with a Gothic one. The transepts were added in 1491. Some things never change. ;-)

The Church of Our Lady in Halberstadt is a fine example of a four towered Romanesque church, dating back to 1005 albeit with changes in the 12th century (addition of the side naves), and again in the 14th century (cross grain vaulted ceiling to replace the former timber one). Even younger alterations during the 19th century historicism (wannabe Middle Ages style) have partly been deconstructed in the renovations post-WW2.

Huysburg Monastery was founded in 1080 as Benedictine monastery by Bishop Burchard of Halberstadt. It fell to the secularization in 1804, but became a monastery again in 1972; the only Benedictine monastery in the GDR. The church is a Romanesque basilica (unfortunately with Baroque bling inside). Other buildings have been added over the centuries; some of them serve as guest houses and meeting rooms today.

This cave can be found in the Huy mountain, a sandstone ridge now grown with beeches. There is a legend about an abducted maiden who was forced to work for a gang of evil robbers until she managed to escape, alert the village and give the guys their just dessert. The place has been lived in, maybe even by some unsavoury guys, but there are no documents about a veritable brigand gang harrassing the surroundings for years.

Here we got some 19th century Hobbit dwellings. *grin* They can be found in several places in the village of Langenstein. Some of these go back to the 12th century and were successively expanded. The last inhabitant left his cave in 1916. They were actually up to the living standard of the time, cool in summer and warm enough in winter thanks to ovens. The toilets were outside in the (in)famous plank huts.

The caves are of varying size; the average is 30 square metres for a family, with a kitchen and larder, a living room, and sleeping quarters. The caves were not poor man's hovels, but respectable housings for the working class. Several of them have been lovingly restored and equipped with old-fashioned furniture.

This crazy way leads through the red sandstone and musselkalk of the Huy mountain up to the remains of a castle. There are caves here, too, those dating back to the time of the Germanic tribes living here in pre-Roman times. They have been used until the 20th century, but they are larger and less comfortable, with no separate rooms. The last people to live there were some refugees from WW2 (until better places could be found for them).

At the end of the crazy way are some bits of castle wall. Castle Langenstein was built by the bishop of Halberstadt in the 12th century and once was a large and imposing structure covering the entire plateau of the hill. It was destroyed during the thirty Years War and used as quarry afterwards. Today only a section of a wall with the window opening is left. But the view over the land all the way to Halberstadt is nice.

These are the outlines of a longhouse from the early Bronze Age (2300 - 1800 BC) near Benzingerode. When the new interstate was built, lots of prehistoric finds came up that are now spread to several museums. The area is not so far from the place where the famous Nebra disc has been found - quite a busy place some 4000 years ago. There are several menhirs in the surrounding fields, but no longer accessible. Since people kept stomping over the fields with no regard for the corn, the farmers fenced them in.

This bit of geological fun can be found in the Huy mountain ridge. Glacier mills are the result of cracks in the ground where glaciers slowly pushed forward. Melting water and small debris would run down those cracks and over time, carve canons, where the small stones washed out kettle shaped holes, the glacier mills. The mills in the Huy date back to the Saalian stage of the Ice Ages (352,000 - 130,000 years ago) and are the only ones to be found in Germany outside the Alps.

A typical Harz river, clear and cold, running over boulders.

2008

Our journey to the Harz and Quedlinburg was fun, but also very hot with about 32°C during the day and lots of sunshine. Fortunately, the nights were a bit cooler since the temperature in the Harz drops somewhat more than in Göttingen (which can be a steaming soup bowl in summer) and the hotel was situated at a little river that brought a cool breeze in the evenings.

There were several beers with my name on them every evening, and they just evaporated somehow. I don't even want to begin and try to figure out how many litres of water I drank; it must have been a small lake. Ice cream is a good thing on hot days, too, especially iced coffee with vanilla ice cream and dab of whipped cream on top.

But it was definitely fun, including the climbing of some rocks in sandals. I'm the proverbial German when it comes to wearing shoes unsuitable for mountains. Maybe I should volunteer as test person for sandals - if they survive the ways I walk, they will survive about anything.

The Harz was always a politically important area throughout history, not at least because it's rich in ore, and so Mediaeval times saw a lot of castles on the tops of those hills and mountains. Many of the about 500 Harz castles have left nothing more behind than some tumbled stones and traces in the ground that point to an ancient trench or earthen wall, but some are still formidable ruins or even reconstructed to mirror their former beauty.

Germany can be very green, too.

Many German castles are less grand than the Norman castles because space on summits is more limited, but their owners and the architects sometimes got very inventive when it came to making the land - or rather, the bedrock - part of the castle construction. The Regenstein with its part natural, part artificial caves surrounding the keep is a fine example.

Not all castles were in the focus of the great history the way the Harzburg (which I hope to see in August) was, but they all have their stories. And legends. The Harz is rich in legends, and you'll learn some in the time to come.

I've got some Romanesque churches for you as well. There is a road - or rather, a number of connected roads all over Germany - leading to the most interesting Romanesque buildings. You can visit churches and a few castles and other buildings all the way from the Alpes to the Baltic Sea coast, following the Strasse der Romanik.

I got only inside views of this one because the towers were wrapped in scaffolding, and since the catherdral sits on a hill, surrounded by other buildings, the towers are pretty much the only thing you can see. The inside has been renovated already and looks a lot better than last time I was there, but unfortunately, the crypt is still closed.

This one is really beautiful and in good condition. Nice and cool inside as well. *grin* Churches are a good place to visit on a hot day.

Both Quedlingburg and Gernrode were Canoness Chapters for noble ladies who would live more or less like nuns only without taking permanent vows. That way they could leave and marry if family politics changed. But some stayed all their life and the Abbesses, esp. the ones of Quedlinburg, held a lot of power.

Not much remains of the Konradsburg Monastery, only the choir of the church and the crypt which is undergoing restoration (almost finished, so I got some good photos). But the history behind it is interesting; Konradsburg is the only monastery that started off as castle (Burg = castle, you've seen that word in several names).

Remains of a 12th century Cisterciensian monastery. The cloister and some of the outhouses have been preserved and today house a museum for music instruments, a school, and a restaurant.

I want a garden like that.

One of the many shots I took of that one. I love running water.

Views

Of course, I used the high vantage points on the mountain peaks of the Harzburg and the Ilsestein to take some photos, and despite the somewhat hazy atmosphere of early autumn, a number of them turned out fine.

View from the Harzburg towards the Brocken - the mist-veiled mountain in the background - in the morning sun. The Brocken (1142 m) is the highest mountain in the Harz and the central meeting place of German witches on Walpurgis Night. The place is a bit too touristy for my taste so I haven't been to the top yet. During the time of the German division the Brocken was Russian military zone and not accessible from either West or East.

Another view from the Harzburg. Fall has arrived in the Harz already, with crisp mornings, mists rising from the vales, the first brown leaves dancing in the breeze, and a lower sun tinting the trees golden like a last greeting of summer. A farewell.

On the other side of the Harzburg, the view goes towards the Norddeutsche Tiefebne, a mostly flat area that stretches all the way from the Harz to the Baltic Sea. In the distance, though beyond view, lies Braunschweig, the main seat of Heinrich the Lion; and further to the north-east Magdeburg and Berlin. The town at the foot of the mountain is Bad Harzburg, a popular spa town.

This one is less spectacular but pretty. The stones to the right are not a natural formation this time, but the remains of a curtain wall. The photo was taken at Stapelburg Castle, one of the smaller fortresses in the Harz. I got a few pics of what is left of the main hall and the trenches, so I'll leave a more detailed description to another post.

Another view from the Paternoster cliffs on the Ilsestein mountain. The blueish shadow to the left is the Brocken again - you can't miss that big boy from most of the Harz's high vantage points. The entire area is a National Park today.