My Travel and History Blog, Focussing mostly on Roman and Mediaeval Times

5 Oct 2015

Sub-Marinean Monsters - The Ozeaneum in Stralsund: The North Sea

The tour of the Ozeaneum - follow the little footprints on the floor - will now take us to the North Sea in this second post about the tank displays of the Oceanographic Museum in Stralsund.

Some fish like herring or haddock can be found in both seas, but others have developed special subspecies who can deal with the higher salinity of 3,5%.

Compass jellyfish

This jellyfish is a bit more alien looking. Compass jellyfish also have toxic nematocysts at the end of their tentacles whose discharge can lead to skin irritation. The species can be found in the deeper water off the British and Dutch coasts, but storms sometimes bring them up and onto the shore.

Great Spider Crab

Great spider crabs (Hyas araneus) are indigenous to the North Sea and Atlantic. They live in deeper water (down to at least 50 metres). They are hunters who hide under stones or other places and who, like their Baltic Sea relatives, use algae to cover their shields, until something edible, like a starfish, comes along.

Tank 'Tidal Bassin', weever

This guy may look harmless if a bit grumpy, but it's actually one of the nastier critters hiding in the tidal sands. The weever has a sting on its back that ejects poison into the foot of any hapeless tourist who happens to step on it. The pain and discomfort may be worse than a vasp sting and can lead to an allergic shock.

Coral reef in the Channel, with boar fish

Another of those beautiful coral reefs, this time from the North Sea. The violet ones are called Anthothelia, a deep sea coral that can deal well with cold, dark water. Those red darlings swimming among the corals are boar fish, almost too colourful for the environment - it's what you would expect in the Pacific. But boar fish turn black when they swim into deeper water.

A wreck with new coral and sea urchin colonies

I liked this one just because it looks so pretty. A simulated wreck starting to attract inhabitants of all sorts.

Tank 'Helgoland', catsharks

Those two guys were hanging out in the tunnel-shaped Helgoland tank. The dark colour is due to the dim light; catsharks (also called dogfish) are a bit lighter of colour, with dark spots. But I like the blue version. :-)

Tank 'Scottish Underwater Cave', with a John Dory

This one is not a nice fish to meet if you're a herring. It will suck you right in, literally. John Dorys can evert their mouth very wide and snatch an entire herring. Slurrp. But humans are safe.

Tank 'Open Atlantic', a shoaling of mackerels, with some cod

The last tank is the largest. The 'Open Atlantic' contains 2.6 million litres of water. Too bad I could not find out what the glass plane of that one weighs - it has a size of 50 square metres and is 30 cm thick. It also was the most difficult to photograph because the fish kept either moving too fast, or hiding in the background of the big bassin.

Tank 'Open Atlantic', stingray

Now try to escape the stingray and resurface back in the museum after the trip through the Baltic and North Sea. You can visit a guy from the other hemisphere on the museum roof: one of the ten Humboldt penguins living there (the other ones were hiding in their stone caves).

A curious Humboldt penguin

I hope you liked the little tour through an unknown and alien world. A hot tea or coffee may be in order now.

I could have spent more time in the museum if my itinerary had allowed it, waiting for the perfect shot of some cool fishes.

The tour of the Ozeaneum - follow the little footprints on the floor - will now take us to the North Sea in this second post about the tank displays of the Oceanographic Museum in Stralsund.

Some fish like herring or haddock can be found in both seas, but others have developed special subspecies who can deal with the higher salinity of 3,5%.

This jellyfish is a bit more alien looking. Compass jellyfish also have toxic nematocysts at the end of their tentacles whose discharge can lead to skin irritation. The species can be found in the deeper water off the British and Dutch coasts, but storms sometimes bring them up and onto the shore.

Great spider crabs (Hyas araneus) are indigenous to the North Sea and Atlantic. They live in deeper water (down to at least 50 metres). They are hunters who hide under stones or other places and who, like their Baltic Sea relatives, use algae to cover their shields, until something edible, like a starfish, comes along.

This guy may look harmless if a bit grumpy, but it's actually one of the nastier critters hiding in the tidal sands. The weever has a sting on its back that ejects poison into the foot of any hapeless tourist who happens to step on it. The pain and discomfort may be worse than a vasp sting and can lead to an allergic shock.

Another of those beautiful coral reefs, this time from the North Sea. The violet ones are called Anthothelia, a deep sea coral that can deal well with cold, dark water. Those red darlings swimming among the corals are boar fish, almost too colourful for the environment - it's what you would expect in the Pacific. But boar fish turn black when they swim into deeper water.

I liked this one just because it looks so pretty. A simulated wreck starting to attract inhabitants of all sorts.

Those two guys were hanging out in the tunnel-shaped Helgoland tank. The dark colour is due to the dim light; catsharks (also called dogfish) are a bit lighter of colour, with dark spots. But I like the blue version. :-)

This one is not a nice fish to meet if you're a herring. It will suck you right in, literally. John Dorys can evert their mouth very wide and snatch an entire herring. Slurrp. But humans are safe.

The last tank is the largest. The 'Open Atlantic' contains 2.6 million litres of water. Too bad I could not find out what the glass plane of that one weighs - it has a size of 50 square metres and is 30 cm thick. It also was the most difficult to photograph because the fish kept either moving too fast, or hiding in the background of the big bassin.

Now try to escape the stingray and resurface back in the museum after the trip through the Baltic and North Sea. You can visit a guy from the other hemisphere on the museum roof: one of the ten Humboldt penguins living there (the other ones were hiding in their stone caves).

I hope you liked the little tour through an unknown and alien world. A hot tea or coffee may be in order now.

I could have spent more time in the museum if my itinerary had allowed it, waiting for the perfect shot of some cool fishes.

22 Sept 2015

Nature, some Very Old Tombs, and a Slavic Ringwall

The Baltic Sea coast and the landscape further inland are beautiful in a way different from the mountains of the Harz and Meissner or along the Weser; places I've frequently blogged about. But I love the northern part of Germany and the sea very much.

Hiddensee island, the coast of the Baltic Sea

Offshore of Stralsund are two islands, Rügen and Hiddensee. Fortunately, one day turned out to be sunny, and I decided to take a ship over to Hiddensee and do some hiking in the dunes, juniper heath and beech forests of this lovely island.

Hiddensee, the lagoon side seen from the lighthouse

There are no cars on Hiddensee (except for an ambulance and a small school bus) so you have to use your feet, a bicycle, or a horse coach to get around. I'd read about Hiddensee in a children's book many years ago and was devastated when my parents told me it was in the GDR and we could not go there. Well, there's no longer a GDR and now I could go there.

Riparian forest at the river Wakenitz

The Wakenitz is a river which springs from the Ratzeburg Lake and confluences into the Trave near Lübeck. The river had been the border between West-and East-Germany and therefore remained a wilderness with riparian forests framing its shores. There's a boat tour from the Ratzeburg Lake to Lübeck which turned out to be one of the most beautiful ones I ever did.

The bay of Wismar, seen from the cog Wissemara

Another fun ship tour I did was an afternoon out at sea on the reconstruced cog Wissemara. It is modeled after a wreck dating to ~1350 which had been found near the Poel peninsula in 1999. When I was in Wismar in 2004, I came across the construction site of the cog, so being able to sail with her now was a special experience.

One of several Neolithic burials near Grevesmühlen

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is rich in tombs from the Neolithic Funnelbeaker culture (3,500 - 3,200 BC). We got the simple dolmen type, the great dolmen, the passage grave, and the long barrow. The boulders used to erect them are glacial erratics. There are several burial sites in the Everstorf Forest near Grevesmühlen.

The dolmen called Devil's Oven

Those giant stone structures led to local legends. The dolmen above is called Devil's Oven and the matching long barrow stone setting is the devil's bed. Often, the extended dolmen are refered to as giant's tombs with the usual legend about how someone tricked the giant and killed him.

Open air museum Gross-Raden, the gate of the settlement

Another interesting place was the open air museum in Gross-Raden, a reconstructed Slavic settlement with ringwall castle from the 10th century, which has been built on the original site. Excavations had taken place 1973-80 and the reconstruction started a few years later; the museum opened in 1987.

Gross-Raden, the ringwall fortress

Like in Haithabu, not all the houses have been reoconstructed, but Gross-Raden has more buildings, including a temple. The most interesting feature is the ringwall fortress - an earthen rampart crowned by a timber palisade - with its impressive tunnel door.

Humboldt penguin in the Ozeaneum Stralsund

The Ozeaneum in Stralsund shows the underwater world of the Baltic Sea and the North Sea in a series of aquariums and other displays. It was an interesting way to spend a rainy evening. The Humboldt penguins don't belong in the north, of course, but they're a cute addition.

Another view of the bay of Wismar seen from the cog

Finally another shot taken from the stern of the cog. The sun had decided to come out after a very wet morning and give me some nice blue water and sky.

The Baltic Sea coast and the landscape further inland are beautiful in a way different from the mountains of the Harz and Meissner or along the Weser; places I've frequently blogged about. But I love the northern part of Germany and the sea very much.

Offshore of Stralsund are two islands, Rügen and Hiddensee. Fortunately, one day turned out to be sunny, and I decided to take a ship over to Hiddensee and do some hiking in the dunes, juniper heath and beech forests of this lovely island.

There are no cars on Hiddensee (except for an ambulance and a small school bus) so you have to use your feet, a bicycle, or a horse coach to get around. I'd read about Hiddensee in a children's book many years ago and was devastated when my parents told me it was in the GDR and we could not go there. Well, there's no longer a GDR and now I could go there.

The Wakenitz is a river which springs from the Ratzeburg Lake and confluences into the Trave near Lübeck. The river had been the border between West-and East-Germany and therefore remained a wilderness with riparian forests framing its shores. There's a boat tour from the Ratzeburg Lake to Lübeck which turned out to be one of the most beautiful ones I ever did.

Another fun ship tour I did was an afternoon out at sea on the reconstruced cog Wissemara. It is modeled after a wreck dating to ~1350 which had been found near the Poel peninsula in 1999. When I was in Wismar in 2004, I came across the construction site of the cog, so being able to sail with her now was a special experience.

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is rich in tombs from the Neolithic Funnelbeaker culture (3,500 - 3,200 BC). We got the simple dolmen type, the great dolmen, the passage grave, and the long barrow. The boulders used to erect them are glacial erratics. There are several burial sites in the Everstorf Forest near Grevesmühlen.

Those giant stone structures led to local legends. The dolmen above is called Devil's Oven and the matching long barrow stone setting is the devil's bed. Often, the extended dolmen are refered to as giant's tombs with the usual legend about how someone tricked the giant and killed him.

Another interesting place was the open air museum in Gross-Raden, a reconstructed Slavic settlement with ringwall castle from the 10th century, which has been built on the original site. Excavations had taken place 1973-80 and the reconstruction started a few years later; the museum opened in 1987.

Like in Haithabu, not all the houses have been reoconstructed, but Gross-Raden has more buildings, including a temple. The most interesting feature is the ringwall fortress - an earthen rampart crowned by a timber palisade - with its impressive tunnel door.

The Ozeaneum in Stralsund shows the underwater world of the Baltic Sea and the North Sea in a series of aquariums and other displays. It was an interesting way to spend a rainy evening. The Humboldt penguins don't belong in the north, of course, but they're a cute addition.

Finally another shot taken from the stern of the cog. The sun had decided to come out after a very wet morning and give me some nice blue water and sky.

12 Sept 2015

Hunting more Hanseatic League

I'll be off again to find more Hanseatic League related things, and some more brick cathedrals and other buildings in Stralsund, Lüneburg, and Lübeck once more, where the new Hansa Museum has now opened.

Lübeck, houses at the Trave, with a sailing ship in the foreground

Also on the intinerary is Schwerin and probably another open air museum or two. Let's hope the weather holds; rain makes for dreary photos like the ones here (just well it was the only bad day during my spring tour).

Lübeck's old town, seen from the outer harbour

I'll be back in about ten days, hopefully with new photo booty.

You can check the map linked in the post below to find the places.

I'll be off again to find more Hanseatic League related things, and some more brick cathedrals and other buildings in Stralsund, Lüneburg, and Lübeck once more, where the new Hansa Museum has now opened.

Also on the intinerary is Schwerin and probably another open air museum or two. Let's hope the weather holds; rain makes for dreary photos like the ones here (just well it was the only bad day during my spring tour).

I'll be back in about ten days, hopefully with new photo booty.

You can check the map linked in the post below to find the places.

6 Sept 2015

Surviving as Sacrifice - The Nydam Ship

The peninsula (1) between Baltic and North Sea is a typical terminal moraine landscape which developed after the last Ice Age (~ 11,700 BC). Fertile marshlands - albeit prone to flooding - in the west are followed by the sandy geest formation in the middle, and the uplands to the east. Those are a landscape of low hills and lakes, bays and firths, and bogs. The land had been settled since the Neolithic Age, but it would be the people from the Iron Age who left behind the most interesting remains in form of bog sacrifices. Among those is the famous Nydam Ship.

The Nydam Ship

The Nydam Ship - a rowing boat without additional sail - dates to AD 320. She is made of oak timber, 23.7 metres long and 3.5 metres wide midships; with space for 32 men to row her (2).

It is by ships like this the Angles and Jutes came to England. Imagine a fleet of those, some even larger, arriving at the shore close to your village, the crews brandishing the spears and swords also found in the bog. In AD 320 you could at least hope the local Roman garrison was on alert, but a hundred years later you might wonder if the Picts were really that bad. *wink*

The Nydam Ship from a different angle

The Danish archaelogist Conrad Engelhardt discovered the Nydam Ship in a bog near Sønderborg in Denmark (3) in 1863. It was one of several ships that had been deposited in a lake between ~ AD 200-450. Another oak ship found at the site had been cut to pieces, but this one remained complete. A third find consisted of a complete ship made of pine, but it was lost during the Schleswig War in 1864. Parts of another, even larger oak ship have been discovered in 2011, but there are currently no plans to salvage it (4). The ships have been buried with lots of weapons and arms in what had then been a shallow lake. The lake silted over and the developing peat bog offered ideal conditions for the preservation of both wood and metal.

Seen from the 'bow'

When the ship was salvaged, some parts were missing or in such a bad shape that they had to be replaced with new ones when the ship was salvaged and restored. But the hull of the Nydam ship survived pretty much intact. It was constructed in clinker technique with overlapping planks, or strakes, above the keel. They were fixed by iron rivets (5). The planks had clefts left standing when they were cut, to which the frames that were lashed. The keel (14.30 metres long and 57 cm wide midships to 20 cm at the ends) was made from one piece of oak, but the strakes were scarved and consisted of more than one plank. The equally shaped bow and stern posts were interlocked with the keel. Caulking was done by wool soaked in sheep's tallow and birchwood pitch.

View from the side

(There is no distinction between starbord and port, because the symmetrical shape of the ship

does not have a clearly defined stern and bow)

The planks have shrunk a bit (from 56 cm to ~ 45 cm) since the boat came in contact with dry air. Its shape is not entirely correct as measurements undertaken in 1995 show: the prow should be higher, the draught deeper and the inside more V-shaped, but due to the altered condition of the wood, the ship cannot be taken apart and reassembled in its correct shape.

View to the inside

Only some bits of the frames - originally single pieces of oak each - survived, though we know by the clefts that they were set p about one metre apart. In the middle of the ship, each plank had two clefts, as does the keel; towards bow and stern the amount of clefts decreases.

It is assumed that the ship was weighted by ballast stones. Recently, parts of a deck, a layer of planks and wickerwork, resting on transverse sticks, have been excavated. A deck between the ribs and the rowing benches would have been necessary for the rowers to put their full power to the oars. The rowing benches are reconstructed as well; they were held by vertical wooden supports and about 30 cm wide (smaller in the middle). The ship would have required 15 oarsmen on each side.

Rowlocks fixed to the gunwale

The gunwale on the 'port' side and the rowlocks also survive mostly in fragments. The rowlocks are interesting because they were crafted separately and latched to the gunwale. The rowlocks were made of forked branches from alder and birch, woods that are soft enough to counter the pressure from the hard ashen oars, and they could be easily replaced in case of wear. The second, chopped up oak boat found in the Nydam bog had its rowlocks cut into the oaken gunwale.

Engelhardt only discovered fragments of oars, but a dig in the 1990ies recovered about 20 oars in a pretty good condition. Some of them are assumed to have belonged to the Nydam Ship. They were made from radially split stem wood of the ash, about 3 metres long and with slim blades. Their shape and the short horizontal distance between rowlocks and thwart points at a rowing technique with short, quick strokes; different from later Viking ships.

Two restored original rowlocks on display in the museum

The side oar attached to the ship is a copy, but the original blade survived albeit in bad condition. It is 55 cm wide with a sharp aft edge and a thicker, rounded fore edge.

Since both the steering oar and the rowlocks are only attached by ropes, they could be shifted to change the direction of the ship with its symmetrical bow/stern, though we don't know if that was actually done (fe. on a river too small to turn the ship).

Remains of oars and frames discovered in 1863

You may have noted the carved heads on the photos; their light coloured wood sticks out in contrast to the dark boat. The bearded, cap wearing heads also have been discovered during the 1990ies dig. They rested on posts and were likely attached to the gunwale the way they are displayed today. Their function is not entirely clear.

The finds also included several hand bailers. The best preseved original is currently shown in Copenhagen. Remains of rope have been found as well. Parts of an iron anchor discovered by Engelhardt are lost today, but some drawings of the finds exist.

Reconstructed hand bailer

Whoever built the Nydam Ship had taken a close look to Roman ships from the time. Contact was likely established at the Dutch coast which was then part of the Roman province of Germania inferior, or in Britain. The clinker technique and the caulking with textiles were used by the Romans, as well as the frames to strengthen the hull, and the scarfing of bow and stern to the keel. The anchor fragments show Roman influence as well. I wonder why the people who built the Nydam Ship did not also copy the concept of having a sail in addition to the oars (6).

View to the inside with rowing benches

The Nydam Ship was built ~ AD 320 according to dendrochronological dating, and deposited in the bog in ~ AD 350. But after her discovery in 1863, her journey was not at an end, due to the political situation. Engelhardt prepared the ship and other finds for an exhibition in Flensburg, but the Schleswig War between Denmark and Prussia in 1864 forced him to store the ship in an attic. After the war, the town of Flensburg and Engelhardt's collection were given to Prussia. The ship was moved to Kiel where it again languished in an attic. It took until 1925 to present the ship and the other finds in the Museum vaterländischer Alterthümer in Kiel. During WW2 the Nydam Ship was removed to a lake near Mölln (south of Lübeck) where it was hidden on a barge. After the war, Denmark claimed the ship and the other Nydam finds since the bog lies on Danish territory, but the Allies allowed it to remain in Germany. The ship was moved to Schleswig where it is exhibited since 1947. It got a new hall in 2013 (7)

Another view from the side

A new excavation campaign was launched by the Danish National Museum (Institute of Maritime Archaeology) from 1989 to 1997 in order to look for remains missed by Engelhardt and new finds. The campaign was pretty successful and Copenhagen got its share of interesting things from the bog. But the main exhibition is still the one in the State Archaeological Museum in Gottorf Palace in Schleswig. Including lots of weapons I'm going to present in a future post.

View from the bow with the steering oar

Footnotes

1) You can find Hamburg easily. North from there right into the peninusla, you will come across Schleswig and Flensburg (and, slightly east of Flensburg, Sønderburg with the Nydam Bog). North-east of Hamburg you'll touch Lübeck and if you go east from there along the coast, you'll come across Wismar all the way to Stralsund, the great towns of the Hansa League. South of Lübeck is Lüneburg which I've mentioned several times as possession of the Welfen dukes of Braunschweig.

2) I've found a crew of 45 mentioned on the internet, but I rather rely on the book by Abegg-Wigg.

3) Today's borders. The Schleswig peninsula was contested between Germany and Denmark for centuries, the frontiers moving to and fro with several wars.

4) The ship is larger and older than the Nydam Ship. Modern Archaeology doesn't always need to dig big holes and drag everything out to gain information, and therefore the ship will remain as long as the bog is the best way to preserve it.

5) The rivets have been replaced with new ones, but in case of the bog conserved Nydam Ship iron doesn not pose the same danger to the timber as in the salt water conserved Vasa.

6) It would be interesting to compare the Nydam Ship with the remains of the older one still in the bog and check that one for Roman influences, or lack thereof.

7) The Nydam Ship was lent to Copenhagen in 2003/04.

Literature

Angelika Abegg-Wigg: Das Nydamboot - versenkt, entdeckt, erforscht. Schleswig, 2014

Michael Gebühr: Nydam und Thorsberg, Opferplätze der Eisenzeit. Schleswig, 2000

The peninsula (1) between Baltic and North Sea is a typical terminal moraine landscape which developed after the last Ice Age (~ 11,700 BC). Fertile marshlands - albeit prone to flooding - in the west are followed by the sandy geest formation in the middle, and the uplands to the east. Those are a landscape of low hills and lakes, bays and firths, and bogs. The land had been settled since the Neolithic Age, but it would be the people from the Iron Age who left behind the most interesting remains in form of bog sacrifices. Among those is the famous Nydam Ship.

The Nydam Ship - a rowing boat without additional sail - dates to AD 320. She is made of oak timber, 23.7 metres long and 3.5 metres wide midships; with space for 32 men to row her (2).

It is by ships like this the Angles and Jutes came to England. Imagine a fleet of those, some even larger, arriving at the shore close to your village, the crews brandishing the spears and swords also found in the bog. In AD 320 you could at least hope the local Roman garrison was on alert, but a hundred years later you might wonder if the Picts were really that bad. *wink*

The Danish archaelogist Conrad Engelhardt discovered the Nydam Ship in a bog near Sønderborg in Denmark (3) in 1863. It was one of several ships that had been deposited in a lake between ~ AD 200-450. Another oak ship found at the site had been cut to pieces, but this one remained complete. A third find consisted of a complete ship made of pine, but it was lost during the Schleswig War in 1864. Parts of another, even larger oak ship have been discovered in 2011, but there are currently no plans to salvage it (4). The ships have been buried with lots of weapons and arms in what had then been a shallow lake. The lake silted over and the developing peat bog offered ideal conditions for the preservation of both wood and metal.

When the ship was salvaged, some parts were missing or in such a bad shape that they had to be replaced with new ones when the ship was salvaged and restored. But the hull of the Nydam ship survived pretty much intact. It was constructed in clinker technique with overlapping planks, or strakes, above the keel. They were fixed by iron rivets (5). The planks had clefts left standing when they were cut, to which the frames that were lashed. The keel (14.30 metres long and 57 cm wide midships to 20 cm at the ends) was made from one piece of oak, but the strakes were scarved and consisted of more than one plank. The equally shaped bow and stern posts were interlocked with the keel. Caulking was done by wool soaked in sheep's tallow and birchwood pitch.

(There is no distinction between starbord and port, because the symmetrical shape of the ship

does not have a clearly defined stern and bow)

The planks have shrunk a bit (from 56 cm to ~ 45 cm) since the boat came in contact with dry air. Its shape is not entirely correct as measurements undertaken in 1995 show: the prow should be higher, the draught deeper and the inside more V-shaped, but due to the altered condition of the wood, the ship cannot be taken apart and reassembled in its correct shape.

Only some bits of the frames - originally single pieces of oak each - survived, though we know by the clefts that they were set p about one metre apart. In the middle of the ship, each plank had two clefts, as does the keel; towards bow and stern the amount of clefts decreases.

It is assumed that the ship was weighted by ballast stones. Recently, parts of a deck, a layer of planks and wickerwork, resting on transverse sticks, have been excavated. A deck between the ribs and the rowing benches would have been necessary for the rowers to put their full power to the oars. The rowing benches are reconstructed as well; they were held by vertical wooden supports and about 30 cm wide (smaller in the middle). The ship would have required 15 oarsmen on each side.

The gunwale on the 'port' side and the rowlocks also survive mostly in fragments. The rowlocks are interesting because they were crafted separately and latched to the gunwale. The rowlocks were made of forked branches from alder and birch, woods that are soft enough to counter the pressure from the hard ashen oars, and they could be easily replaced in case of wear. The second, chopped up oak boat found in the Nydam bog had its rowlocks cut into the oaken gunwale.

Engelhardt only discovered fragments of oars, but a dig in the 1990ies recovered about 20 oars in a pretty good condition. Some of them are assumed to have belonged to the Nydam Ship. They were made from radially split stem wood of the ash, about 3 metres long and with slim blades. Their shape and the short horizontal distance between rowlocks and thwart points at a rowing technique with short, quick strokes; different from later Viking ships.

The side oar attached to the ship is a copy, but the original blade survived albeit in bad condition. It is 55 cm wide with a sharp aft edge and a thicker, rounded fore edge.

Since both the steering oar and the rowlocks are only attached by ropes, they could be shifted to change the direction of the ship with its symmetrical bow/stern, though we don't know if that was actually done (fe. on a river too small to turn the ship).

You may have noted the carved heads on the photos; their light coloured wood sticks out in contrast to the dark boat. The bearded, cap wearing heads also have been discovered during the 1990ies dig. They rested on posts and were likely attached to the gunwale the way they are displayed today. Their function is not entirely clear.

The finds also included several hand bailers. The best preseved original is currently shown in Copenhagen. Remains of rope have been found as well. Parts of an iron anchor discovered by Engelhardt are lost today, but some drawings of the finds exist.

Whoever built the Nydam Ship had taken a close look to Roman ships from the time. Contact was likely established at the Dutch coast which was then part of the Roman province of Germania inferior, or in Britain. The clinker technique and the caulking with textiles were used by the Romans, as well as the frames to strengthen the hull, and the scarfing of bow and stern to the keel. The anchor fragments show Roman influence as well. I wonder why the people who built the Nydam Ship did not also copy the concept of having a sail in addition to the oars (6).

The Nydam Ship was built ~ AD 320 according to dendrochronological dating, and deposited in the bog in ~ AD 350. But after her discovery in 1863, her journey was not at an end, due to the political situation. Engelhardt prepared the ship and other finds for an exhibition in Flensburg, but the Schleswig War between Denmark and Prussia in 1864 forced him to store the ship in an attic. After the war, the town of Flensburg and Engelhardt's collection were given to Prussia. The ship was moved to Kiel where it again languished in an attic. It took until 1925 to present the ship and the other finds in the Museum vaterländischer Alterthümer in Kiel. During WW2 the Nydam Ship was removed to a lake near Mölln (south of Lübeck) where it was hidden on a barge. After the war, Denmark claimed the ship and the other Nydam finds since the bog lies on Danish territory, but the Allies allowed it to remain in Germany. The ship was moved to Schleswig where it is exhibited since 1947. It got a new hall in 2013 (7)

A new excavation campaign was launched by the Danish National Museum (Institute of Maritime Archaeology) from 1989 to 1997 in order to look for remains missed by Engelhardt and new finds. The campaign was pretty successful and Copenhagen got its share of interesting things from the bog. But the main exhibition is still the one in the State Archaeological Museum in Gottorf Palace in Schleswig. Including lots of weapons I'm going to present in a future post.

Footnotes

1) You can find Hamburg easily. North from there right into the peninusla, you will come across Schleswig and Flensburg (and, slightly east of Flensburg, Sønderburg with the Nydam Bog). North-east of Hamburg you'll touch Lübeck and if you go east from there along the coast, you'll come across Wismar all the way to Stralsund, the great towns of the Hansa League. South of Lübeck is Lüneburg which I've mentioned several times as possession of the Welfen dukes of Braunschweig.

2) I've found a crew of 45 mentioned on the internet, but I rather rely on the book by Abegg-Wigg.

3) Today's borders. The Schleswig peninsula was contested between Germany and Denmark for centuries, the frontiers moving to and fro with several wars.

4) The ship is larger and older than the Nydam Ship. Modern Archaeology doesn't always need to dig big holes and drag everything out to gain information, and therefore the ship will remain as long as the bog is the best way to preserve it.

5) The rivets have been replaced with new ones, but in case of the bog conserved Nydam Ship iron doesn not pose the same danger to the timber as in the salt water conserved Vasa.

6) It would be interesting to compare the Nydam Ship with the remains of the older one still in the bog and check that one for Roman influences, or lack thereof.

7) The Nydam Ship was lent to Copenhagen in 2003/04.

Literature

Angelika Abegg-Wigg: Das Nydamboot - versenkt, entdeckt, erforscht. Schleswig, 2014

Michael Gebühr: Nydam und Thorsberg, Opferplätze der Eisenzeit. Schleswig, 2000

22 Aug 2015

Raising the Wreck - The Vasa Museum in Stockholm, Part 2

After the Vasa sank, the upper parts of her three masts with their rigging were still visible which must have made for a somewhat eerie sight.

I was suprised to learn that attempts to raise the Vasa were made immediately after she went down. The unfortunate captain Söfring Hansson was tasked with coordinating the effort. He likely was grateful for the chance to sort the mess before King Gustav Adolf came visiting in a mood as foul as the letters he had written. "Sorry, your Majesty, she got a bit wet, but we'll give her a brush up and she'll be as good as new, I promise," would have sounded nicer than pointing at the slanted mast tops in the harbour. "There she lies."

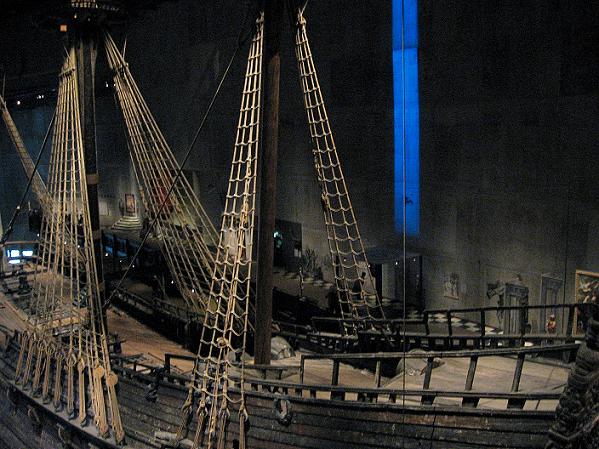

The hull of the ship

Salvaging technology in the 17th century worked like this: Two ships, often just hulks, were placed on both sides of the sunken ship. A number of ropes were sent down and hooked to the ship with the help of special anchors. I could not find details about the process but it may have involved freedivers - we'll later see that those could reach the ground where the Vasa lay. The hulks were then filled with as much water as was safe for them to hold so they would lie deep in the water, the ropes tightened and the water pumped out. When the hulks or ships rose again, they would take the sunken ship up with them. The process was repeated until the wreck could have been transported to shallower waters and then further until she was fully raised above water level. At this early stage, the timber of the Vasa was not yet waterlogged, so the method might have worked.

The first attempt was made by the English engineer Ian Bulmer who succeeded in righting the ship which had sunk sideways; an important first step. But it turned out the Vasa got stuck deeper in the mud by the process, which would cause problems. Mud sucks and increased the weight that pulled on the ship to a point that could not be overcome by 17th century technology. Bulmer's successors, first a Dutch and later a Scottish engineer (1), had no more luck in lifting the Vasa, though they used the largest warships of the fleet for leverage and had extra strong anchors forged to attach to the wreck. In 1640, she was counted as lost.

The main mast with the crow's nest

But some parts could still be salvaged. The top- and topgallant yards and crow’s nests had already been taken down in fall 1628, so they would not be harmed by the ice. Since King Gustav Adolf came back to Stockholm as late as December, the only part still visible were the bare tops of the masts. Later parts of the cordage and spars were brought up; those were valuable goods that could be reused. Some of the decorative figures were also saved.

Some 300 years later, the mud filled parts of the ship turned out to have one advantage; it preserved organic material which is normally lost to decay.

Even more valuable were the cannons which were recovered with the help of a diving bell in 1663-65. The greatest disadvantage of freediving is the short time people can actually work under water because of the way down and back up (in case of the Vasa that was about 30 metres). The time would never be enough to deal with the heavy and unwieldy guns.

Reconstructed crow’s nest

A diving bell is weighted so that the air compresses when the bell is let down, and the divers can go back in and take a fresh lungful several times before the bell has to be lifted, thus strechting the working time under water considerably (2). In the Baltic Sea, the cold proved more of a problem; the divers had to go up and get warm again after 15-20 minutes.

The idea of a diving bell goes back to Aristotle, but the technology was refined only in the 17th century. The bell used with the Vasa was a so-called wet bell with an open bottom of about 130 cm height. A small leaden bench – more or less an extended clapper - was attached so it stuck out 50 cm below the bell, where the diver could sit on the way up and down with his head and shoulders in the air bubble. The bell was moved by several men with help of a simple crane. The diver could also bring objects to the surface, though in case of the cannons, ropes were attached to bring them up without use of the bell (see below).

The restored weather deck, seen from the aft

Albrecht of Treileben was a nobleman from Brandenburg in Germany who had participated in the Thirty Years War as officer in the Swedish army. He later traveled around Europe and took up scientific studies. In the 1650ies Treileben and his German associate Andreas Peckell established a diving crew with divers from Sweden and Finland in Gothenburg which successfully salvaged parts of another ship in presence of the Lord High Steward Per Brahe. Treileben applied to King Karl X Gustav for the right to salvage parts of the Vasa (3) in 1658, but it would take until the regency of Brahe (for the underage Karl XI; 4) for Treileben to get the commission (1603).

The Italian priest, natural scientist, and traveler Francesco Negri (1624 -1698) left an eyewitness account of the salvaging in his travelogue of a journey to the north that led him as far as the North Cape, the Viaggio Settentrionale. We owe him the description of the bell and some information he obtained from one of the divers. Visibility under water was acceptable, the diver said; the air in the bell would have been enough for half an hour, but the cold was the greatest problem albeit the divers wore special suits of oiled leather.

The cannons were decorated as well - the three remaining cannons salvaged in the 20th century

The weather deck was dismantled in parts to get at the cannons of the upper gun deck, but salvaging the ones from the lower gun deck proved more tricky. The team used big gripper tongs maneouvered by ropes from the crane that also worked the diving bell. The diver would fix the claws of the tong to the shaft of the cannon. The ropes leading to the surface put pressure on the thong, the claws tightened, and the cannon could be dragged out of its port, probably with some guidance by the divers. It seemed to have been a pretty smooth process since the gun ports show very little damage. Pity they didn’t use the same method for the upper gun deck.

The work was overshadowed by a big quarrel between Treileben and his associate Peckell. Treileben had Peckell forcefully emitted from the docks and kept all his tools. Treileben obviously wanted to be the only one to gain the financial win, and because he had friends in the Royal Council, he thought he’d get away with it. But Peckell managed to get a trial which condemned Treileben to pay Peckell his share and reparation for the confiscated tools (5).

The guns were sold to Lübeck and Hamburg (6), the main markets for cannons. Some of them were then sold to the Danish army which was at war with Sweden - yet again - during the Scanian War (1675-79). Denmark wanted Scania back, which it had to cede to Sweden in the Treaty of Roskilde in 1160. Sweden lost at sea, Denmark at land, and in the end nothing much changed (7).

The decorated quarterdeck seen from the side

The Baltic Sea has one advantage: the water is too brackish for the nasty naval ship worm Teredo navalis (8) to thrive, therefore wood survives pretty well. But nevertheless, the wreck of the Vasa was subjected to erosion and decomposition during the more than 300 years it lay in Stockholm’s harbor. Fortunately, the hull was held together by wooden nails and thus remained intact, contrary to the thousands of iron bolts that fixed most exterior structures like the beakhead, the quarter galleries, and the decorative figures. Those eroded pretty fast so that the parts fell into the mud – which proved a good thing since the mud conserved the timber so well that traces of the original colours and gilding can still be found.

The surface of the hull eroded to some extent, but never so badly that the wreck was in danger of collapsing. The worst damage here was done by the recovering of the cannons on the upper deck. Treileben also salvaged some 30 cartloads of timber which likely included the - still missing - figures, intact planks and parts of the standing rigging. In the 19th century, at least one ship anchored above the Vasa; the anchor destroyed part of the quarterdeck.

Model of the raising: first step after the cables had been affixed

The Vasa was never entirely forgotten, but since there was no way to raise the ship before new technologies were developed in the 1950ies, she gained little interest. That changed when the Vasa was rediscovered in August 1956 by the engineer and wreck researcher Anders Franzén and the diver Per Edvin Fälting. The navy, the National Maritime Museum, and the Neptune salvage company worked together in the huge undertaking of raising her.

The method was not so very different from the one used in 1628, but instead of hooks and anchors, six steel cables were put under the ship. Tunnels were cut through the clay with the help of high pressure water jets; a dangerous work for the divers involved since the tunnels were always in danger of collapsing, or the ship might shift her position. Plus diving suits in the 1950ies looked more like space suits, including the big helmet and external air / oxygene support by a hose - surely not as pratical as modern ones. But not accidents happened during the 1300 dives necessary to dig the tunnels and fix the cables.

The cables were connected to lifting pontoons on both sides of the ship. Those work like the hulks or ships used in earlier times, but they are more powerful. The first lift was attempted in August 1959. No one knew if the hull of the ship would hold together under the pressure of getting her out of the sucking mud, but it held. The Vasa was lifted in 18 steps - each gained a meter - from 32 metres (105 foot) to 16 (52 foot) metres and transported to shallower water where it was safer for the divers to prepare her for the final lifts.

A diving suit from the 1950ies

The last lift, when the structure of the hull woud no longer be supported by water, was the most tricky one. The divers cleaned out mud and debris to lighten the ship, and made the hull watertight. All holes caused by the rusted iron bolts which had fallen out were plugged, and the gun ports covered with temporary lids. The cables were replanted with even stronger ones, and the final lifts were done by hydraulic lifting pontoons.

The last steps began in April 1961, and on April 24th, the Vasa broke the surface again after 333 years. In addition to the lifting, underwater pumps were used to get the remaining water out. In early May, she was towed close to the dry dock on Beckholmen and then floated on her own keel for the first time in more than 300 years to enter the dock proper - a bit deep in the water and leaning to port, but float she did.

The Vasa was set up on a concrete pontoon, the hull supported by beams, and the water pumped out of the dock. The ship still rests on the same pontoon today after it had been towed to the new museum complete with its pontoon. The part of the museum where the keel and lower hull sit had been flooded for that purpose.

Model of the raising: final step

A building was erected over the ship, but it left little space between the hull and the walk for the visitors. I've been there in 1980 during my fist visit in Sweden and I was fascinated by the Vasa even though it took a fair bit of imagination to envision her in full splendour. The new museum which opened 1990 is gives a much better impression of the ship.

Several loose parts had already been brought up during the preparations for the raising of the Vasa, and from 1963-67, the ground was systematically checked for more remains. The amount of finds on site and inside the ship amounts to 4,000 pieces. Fitting those back to their proper place on the ship proved a nice jigsaw puzzle, since there are no plans or drawings of the Vasa. Today, 95% of the wood are original timber. Loose finds like possessions of sailors and such are displayed in vitrines.

Quarterdeck decorations, closeup of the Swedish coat of arms

The wood needed preservation once it came in contact with air again. The wreck was sprayed with polyethylene glycol for 17 years (1962-79) until the last bit of water had been replaced so the timber woud not shrink and crack. But it turned out that the structure of the wood has nevertheless weakened during the long stay under water. The problems became visible in the 1990ies. One of the culprits turned out to be the highly corrosive iron, so all iron bolts used to reaffix the parts that had fallen off - like most of the quarterdeck and the bowsprit - since the 1960ies were replaced by stainless steel bolts. To deal with the slight shifting of the hull, adjustable steel wedges were set up to support the ship and further support structures are researched. The temperature and humidity are constantly checked and kept on a level of 18-20°C, relative humidity of 51-59 RF and UV filtered, dim light - a compromise for what is best for the ship and comfortable for visitors. Smaller, removable wooden parts are additionally treated with freeze drying under vacuum.

Restored upper deck, seen from aft

The Vasa is displayed as she would appear in winter storage with the three lower masts stepped and rigged. The topmast and topgallant mast as well as the upper rigging have been lost, but the new museum shows a stylised image of them outside so you can get an idea of the full hight of the ship's 52 metres. One of the few parts of timber that are not original is the mizzenmast (the original could never be found); it consists of wood left outside to season for several years.

The ropes used to rig the ship amount to 4 kilometres. The ship had four sails set when she sank, the remaining six were found in the storage rooms and could be preserved. The smallest is 32 square metres; so it would take too much space to display her with several sails set, and there's no wind in the museum hall to billow them prettily anyway. But the Vasa is impressive even without sails. I'm glad I had the chance to revisit her in 2012.

Another shot of the museum with the stylized masts

Footnotes

1) Willem de Besche and Alexander Forbes, respectively.

2) In modern variants, oxygen is pumped into the bell which further prolongs the time for divers to remain under water.

3) Those rights were held by Alexander Forbes at the time.

4) For the geneaology fans: Karl XI’s mother was another member of the Hostein-Gottorp family, Hedwig Eleonora. She shared in the regency with Brahe.

5) The whole process is well documented in the Royal archives. Peckell actually got more than he asked for since he only claimed the share for the time he actually worked on the site, but he got the share of the entire endeavor. Treileben had overstretched his welcome with his influential friends.

6) I wonder why they were not reused in Sweden, but the contract with Treileben meant that the Swedish government would have to buy them. There may not have been enough money.

7) The Scanian War was basically an aftermath of the Second Northern War (1658-1160). But Scania was only one battlefield during that time. France, Sweden and England were fighting the Netherlands, Brandenburg and House Austria-Hapsburg on a larger scale in the Franco-Dutch War (1672-78).

8) Teredo navalis is actually a marine bivalve mollusc, not a worm. Since the salinity of the Baltic Sea, which started out as proglacial lake 12,000 years ago, increases due to its connection with the North Sea, teredo navalis has started to create havoc in its western parts as well.

Literature

Fred Hocker, Vasa. Stockholm, 2011

Lorelei Randall, Dykarklockan – en resa i tid och rum. Online publication of the KTH Undervattensteknik, 1998

The Vasa Museum's website.

After the Vasa sank, the upper parts of her three masts with their rigging were still visible which must have made for a somewhat eerie sight.

I was suprised to learn that attempts to raise the Vasa were made immediately after she went down. The unfortunate captain Söfring Hansson was tasked with coordinating the effort. He likely was grateful for the chance to sort the mess before King Gustav Adolf came visiting in a mood as foul as the letters he had written. "Sorry, your Majesty, she got a bit wet, but we'll give her a brush up and she'll be as good as new, I promise," would have sounded nicer than pointing at the slanted mast tops in the harbour. "There she lies."

Salvaging technology in the 17th century worked like this: Two ships, often just hulks, were placed on both sides of the sunken ship. A number of ropes were sent down and hooked to the ship with the help of special anchors. I could not find details about the process but it may have involved freedivers - we'll later see that those could reach the ground where the Vasa lay. The hulks were then filled with as much water as was safe for them to hold so they would lie deep in the water, the ropes tightened and the water pumped out. When the hulks or ships rose again, they would take the sunken ship up with them. The process was repeated until the wreck could have been transported to shallower waters and then further until she was fully raised above water level. At this early stage, the timber of the Vasa was not yet waterlogged, so the method might have worked.

The first attempt was made by the English engineer Ian Bulmer who succeeded in righting the ship which had sunk sideways; an important first step. But it turned out the Vasa got stuck deeper in the mud by the process, which would cause problems. Mud sucks and increased the weight that pulled on the ship to a point that could not be overcome by 17th century technology. Bulmer's successors, first a Dutch and later a Scottish engineer (1), had no more luck in lifting the Vasa, though they used the largest warships of the fleet for leverage and had extra strong anchors forged to attach to the wreck. In 1640, she was counted as lost.

But some parts could still be salvaged. The top- and topgallant yards and crow’s nests had already been taken down in fall 1628, so they would not be harmed by the ice. Since King Gustav Adolf came back to Stockholm as late as December, the only part still visible were the bare tops of the masts. Later parts of the cordage and spars were brought up; those were valuable goods that could be reused. Some of the decorative figures were also saved.

Some 300 years later, the mud filled parts of the ship turned out to have one advantage; it preserved organic material which is normally lost to decay.

Even more valuable were the cannons which were recovered with the help of a diving bell in 1663-65. The greatest disadvantage of freediving is the short time people can actually work under water because of the way down and back up (in case of the Vasa that was about 30 metres). The time would never be enough to deal with the heavy and unwieldy guns.

A diving bell is weighted so that the air compresses when the bell is let down, and the divers can go back in and take a fresh lungful several times before the bell has to be lifted, thus strechting the working time under water considerably (2). In the Baltic Sea, the cold proved more of a problem; the divers had to go up and get warm again after 15-20 minutes.

The idea of a diving bell goes back to Aristotle, but the technology was refined only in the 17th century. The bell used with the Vasa was a so-called wet bell with an open bottom of about 130 cm height. A small leaden bench – more or less an extended clapper - was attached so it stuck out 50 cm below the bell, where the diver could sit on the way up and down with his head and shoulders in the air bubble. The bell was moved by several men with help of a simple crane. The diver could also bring objects to the surface, though in case of the cannons, ropes were attached to bring them up without use of the bell (see below).

Albrecht of Treileben was a nobleman from Brandenburg in Germany who had participated in the Thirty Years War as officer in the Swedish army. He later traveled around Europe and took up scientific studies. In the 1650ies Treileben and his German associate Andreas Peckell established a diving crew with divers from Sweden and Finland in Gothenburg which successfully salvaged parts of another ship in presence of the Lord High Steward Per Brahe. Treileben applied to King Karl X Gustav for the right to salvage parts of the Vasa (3) in 1658, but it would take until the regency of Brahe (for the underage Karl XI; 4) for Treileben to get the commission (1603).

The Italian priest, natural scientist, and traveler Francesco Negri (1624 -1698) left an eyewitness account of the salvaging in his travelogue of a journey to the north that led him as far as the North Cape, the Viaggio Settentrionale. We owe him the description of the bell and some information he obtained from one of the divers. Visibility under water was acceptable, the diver said; the air in the bell would have been enough for half an hour, but the cold was the greatest problem albeit the divers wore special suits of oiled leather.

The weather deck was dismantled in parts to get at the cannons of the upper gun deck, but salvaging the ones from the lower gun deck proved more tricky. The team used big gripper tongs maneouvered by ropes from the crane that also worked the diving bell. The diver would fix the claws of the tong to the shaft of the cannon. The ropes leading to the surface put pressure on the thong, the claws tightened, and the cannon could be dragged out of its port, probably with some guidance by the divers. It seemed to have been a pretty smooth process since the gun ports show very little damage. Pity they didn’t use the same method for the upper gun deck.

The work was overshadowed by a big quarrel between Treileben and his associate Peckell. Treileben had Peckell forcefully emitted from the docks and kept all his tools. Treileben obviously wanted to be the only one to gain the financial win, and because he had friends in the Royal Council, he thought he’d get away with it. But Peckell managed to get a trial which condemned Treileben to pay Peckell his share and reparation for the confiscated tools (5).

The guns were sold to Lübeck and Hamburg (6), the main markets for cannons. Some of them were then sold to the Danish army which was at war with Sweden - yet again - during the Scanian War (1675-79). Denmark wanted Scania back, which it had to cede to Sweden in the Treaty of Roskilde in 1160. Sweden lost at sea, Denmark at land, and in the end nothing much changed (7).

The Baltic Sea has one advantage: the water is too brackish for the nasty naval ship worm Teredo navalis (8) to thrive, therefore wood survives pretty well. But nevertheless, the wreck of the Vasa was subjected to erosion and decomposition during the more than 300 years it lay in Stockholm’s harbor. Fortunately, the hull was held together by wooden nails and thus remained intact, contrary to the thousands of iron bolts that fixed most exterior structures like the beakhead, the quarter galleries, and the decorative figures. Those eroded pretty fast so that the parts fell into the mud – which proved a good thing since the mud conserved the timber so well that traces of the original colours and gilding can still be found.

The surface of the hull eroded to some extent, but never so badly that the wreck was in danger of collapsing. The worst damage here was done by the recovering of the cannons on the upper deck. Treileben also salvaged some 30 cartloads of timber which likely included the - still missing - figures, intact planks and parts of the standing rigging. In the 19th century, at least one ship anchored above the Vasa; the anchor destroyed part of the quarterdeck.

The Vasa was never entirely forgotten, but since there was no way to raise the ship before new technologies were developed in the 1950ies, she gained little interest. That changed when the Vasa was rediscovered in August 1956 by the engineer and wreck researcher Anders Franzén and the diver Per Edvin Fälting. The navy, the National Maritime Museum, and the Neptune salvage company worked together in the huge undertaking of raising her.

The method was not so very different from the one used in 1628, but instead of hooks and anchors, six steel cables were put under the ship. Tunnels were cut through the clay with the help of high pressure water jets; a dangerous work for the divers involved since the tunnels were always in danger of collapsing, or the ship might shift her position. Plus diving suits in the 1950ies looked more like space suits, including the big helmet and external air / oxygene support by a hose - surely not as pratical as modern ones. But not accidents happened during the 1300 dives necessary to dig the tunnels and fix the cables.

The cables were connected to lifting pontoons on both sides of the ship. Those work like the hulks or ships used in earlier times, but they are more powerful. The first lift was attempted in August 1959. No one knew if the hull of the ship would hold together under the pressure of getting her out of the sucking mud, but it held. The Vasa was lifted in 18 steps - each gained a meter - from 32 metres (105 foot) to 16 (52 foot) metres and transported to shallower water where it was safer for the divers to prepare her for the final lifts.

The last lift, when the structure of the hull woud no longer be supported by water, was the most tricky one. The divers cleaned out mud and debris to lighten the ship, and made the hull watertight. All holes caused by the rusted iron bolts which had fallen out were plugged, and the gun ports covered with temporary lids. The cables were replanted with even stronger ones, and the final lifts were done by hydraulic lifting pontoons.

The last steps began in April 1961, and on April 24th, the Vasa broke the surface again after 333 years. In addition to the lifting, underwater pumps were used to get the remaining water out. In early May, she was towed close to the dry dock on Beckholmen and then floated on her own keel for the first time in more than 300 years to enter the dock proper - a bit deep in the water and leaning to port, but float she did.

The Vasa was set up on a concrete pontoon, the hull supported by beams, and the water pumped out of the dock. The ship still rests on the same pontoon today after it had been towed to the new museum complete with its pontoon. The part of the museum where the keel and lower hull sit had been flooded for that purpose.

A building was erected over the ship, but it left little space between the hull and the walk for the visitors. I've been there in 1980 during my fist visit in Sweden and I was fascinated by the Vasa even though it took a fair bit of imagination to envision her in full splendour. The new museum which opened 1990 is gives a much better impression of the ship.

Several loose parts had already been brought up during the preparations for the raising of the Vasa, and from 1963-67, the ground was systematically checked for more remains. The amount of finds on site and inside the ship amounts to 4,000 pieces. Fitting those back to their proper place on the ship proved a nice jigsaw puzzle, since there are no plans or drawings of the Vasa. Today, 95% of the wood are original timber. Loose finds like possessions of sailors and such are displayed in vitrines.

The wood needed preservation once it came in contact with air again. The wreck was sprayed with polyethylene glycol for 17 years (1962-79) until the last bit of water had been replaced so the timber woud not shrink and crack. But it turned out that the structure of the wood has nevertheless weakened during the long stay under water. The problems became visible in the 1990ies. One of the culprits turned out to be the highly corrosive iron, so all iron bolts used to reaffix the parts that had fallen off - like most of the quarterdeck and the bowsprit - since the 1960ies were replaced by stainless steel bolts. To deal with the slight shifting of the hull, adjustable steel wedges were set up to support the ship and further support structures are researched. The temperature and humidity are constantly checked and kept on a level of 18-20°C, relative humidity of 51-59 RF and UV filtered, dim light - a compromise for what is best for the ship and comfortable for visitors. Smaller, removable wooden parts are additionally treated with freeze drying under vacuum.

The Vasa is displayed as she would appear in winter storage with the three lower masts stepped and rigged. The topmast and topgallant mast as well as the upper rigging have been lost, but the new museum shows a stylised image of them outside so you can get an idea of the full hight of the ship's 52 metres. One of the few parts of timber that are not original is the mizzenmast (the original could never be found); it consists of wood left outside to season for several years.

The ropes used to rig the ship amount to 4 kilometres. The ship had four sails set when she sank, the remaining six were found in the storage rooms and could be preserved. The smallest is 32 square metres; so it would take too much space to display her with several sails set, and there's no wind in the museum hall to billow them prettily anyway. But the Vasa is impressive even without sails. I'm glad I had the chance to revisit her in 2012.

Footnotes

1) Willem de Besche and Alexander Forbes, respectively.

2) In modern variants, oxygen is pumped into the bell which further prolongs the time for divers to remain under water.

3) Those rights were held by Alexander Forbes at the time.

4) For the geneaology fans: Karl XI’s mother was another member of the Hostein-Gottorp family, Hedwig Eleonora. She shared in the regency with Brahe.

5) The whole process is well documented in the Royal archives. Peckell actually got more than he asked for since he only claimed the share for the time he actually worked on the site, but he got the share of the entire endeavor. Treileben had overstretched his welcome with his influential friends.

6) I wonder why they were not reused in Sweden, but the contract with Treileben meant that the Swedish government would have to buy them. There may not have been enough money.

7) The Scanian War was basically an aftermath of the Second Northern War (1658-1160). But Scania was only one battlefield during that time. France, Sweden and England were fighting the Netherlands, Brandenburg and House Austria-Hapsburg on a larger scale in the Franco-Dutch War (1672-78).

8) Teredo navalis is actually a marine bivalve mollusc, not a worm. Since the salinity of the Baltic Sea, which started out as proglacial lake 12,000 years ago, increases due to its connection with the North Sea, teredo navalis has started to create havoc in its western parts as well.

Literature

Fred Hocker, Vasa. Stockholm, 2011

Lorelei Randall, Dykarklockan – en resa i tid och rum. Online publication of the KTH Undervattensteknik, 1998

The Vasa Museum's website.

9 Aug 2015

The Ship that Never Sailed - The Vasa Museum in Stockholm, Part 1

Well, she did sail some 1,300 metres before she sank on her maiden voyage in August 1628, but that doesn't really count. It was bad news for King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden who commissioned the Vasa, and a worse fate for the 30 people who drowned, but it turned out a good thing for historians, since the wreck could be salvaged in 1961 and gives us a fine example of a warship in the early 17th century.

Today, the Vasa is housed in a new museum in Stockholm which I visited in 2012. The light is dim, the timber of the ship darkened in the process of conservation, and photographing - no flash allowed - proved a bit tricky, but I managed to get enough decent shots for a blogpost or two.

The Vasa (seen from the bow) in her new home, the Vasa Museum in Stockholm

When Gustav II Adolf of Sweden, scion of the Vasa dynasty, became king in 1611, he inherited no less than three wars: with Denmark, Poland, and Russia - a result of the Swedish attempts to expand their power in the Baltic Sea. Plus a cousin who wanted his throne. No wonder the young king (born 1594) needed warships.

The dynastic tangle this time involves mostly Sweden, Germany and Poland. Gustav Adolf's grandfather and founder of the dynasty, Gustav Vasa, had married three times and produced a bunch of sons who became king after him in turn. One of these was Johann III who married Katharina Jagiellonka of the ruling house in Poland (1). Their son was Sigismund King of Poland and some time King of Sweden (1592-1599). Another son was Karl Duke of Södermanland, acting regent since 1599 and king since 1604. He was married to Christina of Holstein-Gottorp (a Danish-German house residing in the palace in Schleswig); the parents of Gustav Adolf.

The stern with the richly decorated raised quarterdeck. The figures had once been brightly painted

Sigismund had been brought up a Catholic and was married to a Hapsburg princess to boot, and the Lutherian Swedish nobility was not keen on having a Catholic king who spent most of his time in Poland anyway. So they told him to go packing - not without fighting a battle first (2) - and Karl became king as Karl IX. When he died in 1611, Gustav Adolf took the throne, aged but seventeen. Sigismund still insisted on his right to the Swedish throne, but he had enough problems in Poland and never posed a real danger for the young king.

The war between Poland and Sweden was about the possession of Livonia (basically what is today Latvia and Estonia). It flamed up several times between 1600 and the Armistice of Altmark in 1629 where Sweden gained part of Livonia, including the important trade town of Riga with its toll income, and a share in the toll of Gdansk, though the town itself remained in Polish possession.

The war with Russia - at times a three sided affair with Poland involved as well - about the possession of Novgorod (a town that had grown rich as member of the Hanseatic League) and southern Finland, ended with a peace treaty and Swedish gain: the Peace of Stolbovo (1617) cut Russia off the Baltic Sea and forced it to trade through harbours mostly controlled by Sweden, which got 20,000 rubles in war indeminity as well, though Russia kept Novgorod.

The hull seen from the stern

The war with Denmark went less well. Denmark controlled the traffic through the Sound between the Baltic and North Sea, and thus the trade routes to England and the Dutch Republic. To avoid their tolls, Karl IX of Sweden tried to establish a northern land route through Lapland to Tromsø and gain access to the North Sea from there. As a result Denmark, which claimed Lapland as well, declared war and conquered Kalmar in 1611.

When Gustav Adolf ascended the throne, he personally led some raids across the Danish border, but Christian IV of Denmark managed to conquer the fortress of Älvsborg (today Gothenburg), the last Swedish hold in the west. But other countries did not want to see Denmark's power growing too strong, and it was King James I of England who pushed the parties to the negotiation table in Knäred in 1613. Lapland came back under Danish control while Sweden would be fred of the Sound toll, though it had to ransom the important harbours of Kalmar and Älvsborg. No wonder Gustav Adolf was keen on getting money.

Sailing right at you with her impressive bowsprit

But Gustav Adolf was not done with wars. In 1618, a war had started on the continent that would become known as the Thirty Years War. It was about religion as well as politics, a Catholic/Imperial league against a Protestant/anti-Imperial union (3). When the Catholic armies began to push deep into Protestant territories in northern Germany, and the emperor Ferdinand II declared the Edict of Restitution (4), Gustav Adolf was worried not only about those sharing his faith, but also about a possible danger of Imperial Hapsburg influence at the Baltic Sea coast. Nor did he like the alliance between his cousin once removed Sigismund of Poland and Sigismund's Hapsburg relations-by-marriage. So Gustav Adolf supported his former enemy and fellow Protestant Christian IV King of Denmark who had taken heavy losses agains the Imperial generals Wallenstein and Tilly. When Wallenstein laid siege to the important coastal town Stralsund, both Gustav Adolf and Christian sent relief troops by sea and forced Wallenstein to abandon the siege (1628).

Closeup of the quarterdeck with its ornaments; in the middle the arms of House Vasa

The rest of the story is well known. In July 1630, Gustav Adolf landed with an army of 13,000 men on the Usedom peninsula and swept through Germany, defeated general Tilly at Breitenfeld, and continued all the way to Munich with an ever increasing army. The emperor Ferdinand II of Hapsburg was obliged to recall Wallenstein whom he had sent into early retirement just a few months before. Wallenstein forced the Swedish-Protestant army to engage in battle at Lützen. King Gustav Adolf, leading his men in person as usual, fell to the bullets of some mercenaries on November 6, 1632. His chancellor Axel Oxenstierna acted as regent for the king's daughter (5). Sweden continued to be involved in the war on German soil which would last another sixteen years until 1648.

Upper deck with parts of the rigging

One ship that would not join in the relief of Stralsund was the unfortunate Vasa. It was a bright Sunday with little wind on August 10, 1628. The Vasa had been rigged; ballast, cannons and ammunition stored, and some 150 crew members taken onboard. Three hundred soldiers were supposed to join later. All gunports (she carried 64 cannons on two gun decks) had been opened.

After the ship had been warped into the waters of the Slussen, four of her ten sails were set. Onlookers ringed the quays and shorelines, a salute was fired, and the Vasa set off for her maiden voyage. But when she reached the lee of the Södermalm Cliffs, a sudden down drought, common in these waters, caught her and she heeled to port. She had been prone to instability to begin with, so she rose but slowly. A second gust made her heel again and now the lower gunports took water. The Vasa sank after having sailed but 1300 metres. Most of the people onboard could save themselves by swimming or clinging to the rigging that was still over the waterline. But 30 unlucky ones inside the ship died; 16 of their skeletons would be found more than 300 years later.

Seen from the bow, with the forecastle deck to the left

The Vasa was one of four ships King Gustav Adolf had commissioned in 1625. He chose the Dutch master shipwright Henrik Hybertsson and his brother Arendt de Groot, who was responsible for the financial part. Henrik was an experienced shipwright and had already worked for Karl IX of Sweden, but he had never built a ship with two gun decks before. At that time, there were no plans and drawings; a shipwright used proportions, rules of thumbs, and his own experience. Unfortunately, Henrik Hybertsson became ill and died in spring 1627. His assistant Hein Jakobsson and his widow Margareta took over.

In January 1628, Gustav Adolf visited the wharf at Skeppsgården. Obviously, no one was aware of any problems with the ship's stability at that point.

Model of the Skeppsgården wharf

Material for the ship came from a number of places: timber - more than a thousand oak trees - from Sweden and Poland (6), iron from Sweden, sail cloth from Holland, tar from Finland, hemp from Latvia. The cannons were cast in Stockholm. They would cost more money than the hundreds of painted and gilded wooden sculptures created in the workshop of Mårten Redtmer that adorned the ship.

A model of the ship with the original colours (zoomed in)

The Vasa was an impressive ship. Her length - including the bowsprit - was 69 metres, the height of the quarterdeck 19,5 metres, the height from keel to the top of the main mast 52 metres. The ship was only 11,7 metres wide at maximum point, though, and the hold for the ballast stones was rather shallow according to Dutch habit. The ten sails would make for 1,275 square metres. The gun decks were supported by half a metres thick beams that added to the weight above the water line.

The bowsprit with a lion decoration

Sea warfare was about to change and cannons became more important. During the centuries before, the aim was to enter an enemy's ship and capture her in hand-to-hand combat; more or less a land battle at sea. This is why there were still 300 soldiers to go with the Vasa, though some of them may have been artillery specialists. There were also stands for musketeers and mounted crossbows on the high decks which would be more useful at closer range.

In the time to come, ships would pass each other and fire with cannons, trying to sink the enemy's ships.

48 of the Vasa's cannons were 24pounders, the rest somewhat smaller. There is some discussion whether they were indeed intended as weapons or more as a means to intimidate an enemy.

Replica of part of a cannon deck in the musem

The first hints at bad stability occured when Captain Söfring Hansson showed the vice admiral Klas Fleming, who acted as contact to the king, that thirty men running to and fro on the upper deck could make the ship sway so badly she'd capsize at the quay. The admiral was overheard to have said he wished the king was there. But he did not act upon his suspicions, and neither did Captain Hansson. The Swedish fleet had lost several ships to a storm in autumn 1625, and the pressure to replace them was great (7). King Gustav Adolf sent letters from Prussia where he fought the Polish, urging to get the ship ready to sail, and obviously no one dared to delay any further.

Upper deck with rigging

(From this angle you can see how slender the ship is compared to its height.)

Of course, King Gustav Adolf was furious when news of the disaster reached him, and demanded that the guilty ones should be punished. An inquest before a tribunal of members of the privy council and admiralty was set up. Captain Hansson swore that the ballast had been properly stowed, the cannons fixed, the crew sober (which was confirmed by the surviving crew members), and blamed the disaster on the shipwright (8). Vice Admiral Fleming said he was no sailor but responsible for the soldiers and did not understand the true measure of the problem, though his remark about wishing the king to have seen the test performed by the captain was repeated by witnesses during the trial. Shipwright Hein Jakobbson, who had taken over from Henrik Hybertsson, said that he had followed the plans of his master, even widened the ship some 40 cm, but that was all he could do to improve her stability. And the king had approved the plans of his master. In the end, no one was found guilty and the blame was laid on the dead Hybertsson. His widow had to sell her shares the wharf due to financial troubles.

(A post about the salvage of the ship can be found here.)

The new Vasa Museum,

the masts standing out above the building show their original height

Footnotes

1) I'll leave it to Kasia to sort out the Polish geneaologies. :-)

2) Stångebro, 1598.

3) The whole matter is too complicated to cover here. The fault lines were not always along religion; for example Catholic France under Richelieu supported the Protestant confederation because it did not want the Spanish-Austrian Hapsburg dynasty to gain even more power, and the Calvinists and Lutherans were at odds more than once.

4) The Edict of Restitution from 1629 restored all lands and possessions secularized after 1555 (Peace of Augsburg that gave the princes the right to decide on the religion in their territories) to the Catholic Church, which meant a vast gain in land and power. Several archbishoprics and about 500 monasteries had to be returned.

5) Gustav Adolf was married to Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg. Their daughter Christina, born 1626, would become Queen of Sweden (1632-1645); she was the last of the Vasa dynasty.

6) Since Sweden was at war with Poland at the time, the timber was traded via Amsterdam.

7) The king then asked for two medium sized ships to be built first, but at the time the timber for the Vasa had already been cut and prepared, so Hybertsson continued with her construction.