My Travel and History Blog, Focussing mostly on Roman and Mediaeval Times

8 Sept 2008

A Fancy Park and Palace

Last week I went to revisit a non-Medieaval place, the Rococo palace Kassel-Wilhelmsthal. The prettiest feature that one offers is the large park, a mix of Rococo and English landscape style, with fountains, lakes, pavillions, alleys, a fake Mediaeval tower, and a few gilded statues. Here's a photo collection.

The great pavillion with artifical 'river'

Reeds in a lake, part of the English garden

The 18th century 'Mediaeval' tower

View from the tower towards the palace (mostly hidden behind the trees)

Artificial lake near the palace

Below we'll have a look at the palace building which - against the rules of landscape architecture of the time - lies in the vale, not on top of the hill.

Wilhelmsthal Palace, front side

Landgrave Wilhelm VIII of Kassel wanted a summer palace, a maison de plaisance, outside the town, and had the construction of Wilhelmsthal Palace started in 1743. But he died before palace and park were finished.

Wilhelmsthal Palace, the so called 'seaside'

The famous Rococo architect François de Cuivilliés the Elder who mostly worked as Bavarian Court architect in Munich, developed the plans of the two storey main building with side wings and guard pavillions. The interior stuccoes and wood carvings were created by Johann August Nahl who had already worked in Berlin and Potsdam for Friedrich the Great; the paintings by Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder. Most of the tapestries and furniture came from England.

Another view from the park

Wilhelmsthal Palace in one of the most important Rococo buildings in Germany, but the palace is in dire need of some fresh paint. I haven't been inside this time, and I only have some vague memories from a visit some twenty years past, but somehow the place has lost some of its splendour. Let's hope there'll be money for renovation.

Last week I went to revisit a non-Medieaval place, the Rococo palace Kassel-Wilhelmsthal. The prettiest feature that one offers is the large park, a mix of Rococo and English landscape style, with fountains, lakes, pavillions, alleys, a fake Mediaeval tower, and a few gilded statues. Here's a photo collection.

Below we'll have a look at the palace building which - against the rules of landscape architecture of the time - lies in the vale, not on top of the hill.

Landgrave Wilhelm VIII of Kassel wanted a summer palace, a maison de plaisance, outside the town, and had the construction of Wilhelmsthal Palace started in 1743. But he died before palace and park were finished.

The famous Rococo architect François de Cuivilliés the Elder who mostly worked as Bavarian Court architect in Munich, developed the plans of the two storey main building with side wings and guard pavillions. The interior stuccoes and wood carvings were created by Johann August Nahl who had already worked in Berlin and Potsdam for Friedrich the Great; the paintings by Johann Heinrich Tischbein the Elder. Most of the tapestries and furniture came from England.

Wilhelmsthal Palace in one of the most important Rococo buildings in Germany, but the palace is in dire need of some fresh paint. I haven't been inside this time, and I only have some vague memories from a visit some twenty years past, but somehow the place has lost some of its splendour. Let's hope there'll be money for renovation.

7 Sept 2008

Villa en suite

I've mentioned that the Wachenheim villa has two sets of baths, assumedly one for the family located inside the main villa, and another for the slaves and farmworkers in the outbuildings. The family bath encompassed 59 square metres, that's pretty much a two room flat today. Talk about luxury. The room behind the cellar you can see on the photo was the warm bath (changed to a hot bath in the 4th century). The original hot bath is to the right where part of the hypocaust heating has been laid open. There had been a whole system of heating tunnels and water and sewage pipes.

Wachenheim villa, the tepidarium (warm bath)

Directly outside the main building is a latrine with water flushing. Since our dear Romans were practical people, they used the used water from the second baths for toilet flushing by building the seats over the drainage pipe which was guided through an open channel under the toilets. The sewage was probably led into a brook near the villa, while the freshwater was taken from a different source. There has been a well far enough from the brook to have offered clean water. We know from Vindobona (Vienna) that a good part of it ran under the ground, especially in parts where frost may have damaged the aquaeducts (and while the Rhineland is warmer than where I live, frost in winter is not impossible). Such systems would not leave many traces today after ploughing the fields for centuries.

Partly reconstructed toilets, in the background part of the second baths

The toilet seats are a reconstruction. Visiting the loo was not the private matter it is today, not only in the military forts but in private households as well. Latrines often had decorated walls, but not enough traces remain of the Wachenheim villa to learn anything about frescoes and mosaics in those buildings. Public toilets also fell victim to a phenomenon today called graffiti which is not as modern as we think, but I doubt the owner of the villa would have allowed dirty jokes on the latrine walls.

I've mentioned that the Wachenheim villa has two sets of baths, assumedly one for the family located inside the main villa, and another for the slaves and farmworkers in the outbuildings. The family bath encompassed 59 square metres, that's pretty much a two room flat today. Talk about luxury. The room behind the cellar you can see on the photo was the warm bath (changed to a hot bath in the 4th century). The original hot bath is to the right where part of the hypocaust heating has been laid open. There had been a whole system of heating tunnels and water and sewage pipes.

Directly outside the main building is a latrine with water flushing. Since our dear Romans were practical people, they used the used water from the second baths for toilet flushing by building the seats over the drainage pipe which was guided through an open channel under the toilets. The sewage was probably led into a brook near the villa, while the freshwater was taken from a different source. There has been a well far enough from the brook to have offered clean water. We know from Vindobona (Vienna) that a good part of it ran under the ground, especially in parts where frost may have damaged the aquaeducts (and while the Rhineland is warmer than where I live, frost in winter is not impossible). Such systems would not leave many traces today after ploughing the fields for centuries.

The toilet seats are a reconstruction. Visiting the loo was not the private matter it is today, not only in the military forts but in private households as well. Latrines often had decorated walls, but not enough traces remain of the Wachenheim villa to learn anything about frescoes and mosaics in those buildings. Public toilets also fell victim to a phenomenon today called graffiti which is not as modern as we think, but I doubt the owner of the villa would have allowed dirty jokes on the latrine walls.

1 Sept 2008

A Curious Cellar

All that travelling around not only gives me plotbunnies, I also have tons of old material I haven't posted yet, and there's always new stuff adding up. So today we'll go back to that Roman villa rustica in Wachenheim I presented last summer.

One of the most interesting features of the Wachenheim villa is the cellar which has been preserved in its original height - probably got filled with rubbish and mud and was missed by the stone filching farmers. With a size of 11.90 x 3.90 metres (46.50 square for those who, like me, suck at maths) it is one of the largest in the Roman settled lands along the Rhine.

View towards the remains of the villa, the roofed area is the cellar

Light came in from six air shafts on the west wall, albeit not very much. The walls had been whitewashed and were decorated with red painted, artificial joints. The Romans liked even their cellars pretty. The three niches in the north wall also date from this first period.

It has been assumed those may have been places for the images of Mithras and his helpers, and the cellar was used as mithraeum, but the usual stone benches on the sides are missing. On the other side, if the cellar was only used as storage room, why build three niches, one large and two smaller ones, that don't look very useful for putting things in other than statues or such. Wooden shelves would have been of more use.

View towards the north wall niches (the air shafts can be seen on the left)

In the 3rd century, the cellar was rebuilt. The eastern wall which today has seven niches as mysterious as the three on the north side was remade, and the cellar was divided into two compartments by a wall.

While the southern room could still be accessed by the stone stairs hiding behind the bush on the photo below, the 'inner' room would have been entered by a wooden staircase from inside the villa. Maybe it was then the room was used as mithraeum; the benches could well have been made of wood and not stone. I've not found out by which arguments the three niches in the north wall are ascribed the first building period, while the east wall ones belong to the second.

View towards the south, on the right side the niches, in the foreground the dividing wall

In the 4th century, the inner room was filled up and covered with a platform for a furnace room (praefurnium), that way the warm bath (tepidarium) changed into a hot bath (caldarium). The new bath was in use until the villa was abandoned in the 6th century.

I wonder if, in case the inner room has indeed been used as mithraeum, this change in architecture came about by a change in the religion of the owners who may have become Christians and wanted to cover up the pagan place.

All that travelling around not only gives me plotbunnies, I also have tons of old material I haven't posted yet, and there's always new stuff adding up. So today we'll go back to that Roman villa rustica in Wachenheim I presented last summer.

One of the most interesting features of the Wachenheim villa is the cellar which has been preserved in its original height - probably got filled with rubbish and mud and was missed by the stone filching farmers. With a size of 11.90 x 3.90 metres (46.50 square for those who, like me, suck at maths) it is one of the largest in the Roman settled lands along the Rhine.

Light came in from six air shafts on the west wall, albeit not very much. The walls had been whitewashed and were decorated with red painted, artificial joints. The Romans liked even their cellars pretty. The three niches in the north wall also date from this first period.

It has been assumed those may have been places for the images of Mithras and his helpers, and the cellar was used as mithraeum, but the usual stone benches on the sides are missing. On the other side, if the cellar was only used as storage room, why build three niches, one large and two smaller ones, that don't look very useful for putting things in other than statues or such. Wooden shelves would have been of more use.

In the 3rd century, the cellar was rebuilt. The eastern wall which today has seven niches as mysterious as the three on the north side was remade, and the cellar was divided into two compartments by a wall.

While the southern room could still be accessed by the stone stairs hiding behind the bush on the photo below, the 'inner' room would have been entered by a wooden staircase from inside the villa. Maybe it was then the room was used as mithraeum; the benches could well have been made of wood and not stone. I've not found out by which arguments the three niches in the north wall are ascribed the first building period, while the east wall ones belong to the second.

In the 4th century, the inner room was filled up and covered with a platform for a furnace room (praefurnium), that way the warm bath (tepidarium) changed into a hot bath (caldarium). The new bath was in use until the villa was abandoned in the 6th century.

I wonder if, in case the inner room has indeed been used as mithraeum, this change in architecture came about by a change in the religion of the owners who may have become Christians and wanted to cover up the pagan place.

26 Aug 2008

Charming Chester

This post was triggered by the mention of a Fantasy Con to be held in Chester next summer I found on Joe Abercrombie's blog. So for him and anyone else who wants to go to Chester, here are some photo impressions I took when I visited the town in May.

Roman Garden in the morning sun

Not exactly a Roman garden, but a garden decorated with genuine and reconstructed Roman pillars, statues and other artifacts. A pretty little park directly behind the remains of the amphitheatre.

Half timbered houses

Not all of them are Medieaval, though. Chester is very much a Victorian image of the Middle Ages, but there are genuine remains as well. Today the centre with its pretty white and black houses is a tourist magnet and giant shopping mall - only a lot more beautiful than usual.

More old(ish) houses in the centre

You see, it's impossible to get pics without people, and on a bank holiday that was even more a problem. Chester was rather crowded.

Walk on the town wall

The town walls surrounding the centre of todays Chester, built on Roman remains and enhanced in Medieaval times, later repaired after having been damaged in the Civil War, are the most complete in an English town. You can walk around town on top of the walls.

Chester Cathedral, interior

One of the remaining Mediaval buildings is the cathedral, not as large as the York Minster but still very impressive, especially inside. A peaceful place after the crowds in the streets.

Victorian houses at the Dee river

The Victorians loved Chester, and the townside bank of the river is framed with their fancy houses. A river cruise on the Dee (you know how much I love river cruises, so of course, I took one) is a travel back in time.

This post was triggered by the mention of a Fantasy Con to be held in Chester next summer I found on Joe Abercrombie's blog. So for him and anyone else who wants to go to Chester, here are some photo impressions I took when I visited the town in May.

Not exactly a Roman garden, but a garden decorated with genuine and reconstructed Roman pillars, statues and other artifacts. A pretty little park directly behind the remains of the amphitheatre.

Not all of them are Medieaval, though. Chester is very much a Victorian image of the Middle Ages, but there are genuine remains as well. Today the centre with its pretty white and black houses is a tourist magnet and giant shopping mall - only a lot more beautiful than usual.

You see, it's impossible to get pics without people, and on a bank holiday that was even more a problem. Chester was rather crowded.

The town walls surrounding the centre of todays Chester, built on Roman remains and enhanced in Medieaval times, later repaired after having been damaged in the Civil War, are the most complete in an English town. You can walk around town on top of the walls.

One of the remaining Mediaval buildings is the cathedral, not as large as the York Minster but still very impressive, especially inside. A peaceful place after the crowds in the streets.

The Victorians loved Chester, and the townside bank of the river is framed with their fancy houses. A river cruise on the Dee (you know how much I love river cruises, so of course, I took one) is a travel back in time.

24 Aug 2008

Feeling Better

but stiill pretty tired. Thank you all for the well wishes. That was one evil bug I caught there.

I have another fun pic for you. When I visited Caerphilly Castle, I came across a reenactment company demonstrating the use of muskets, archery and sword fighting. I managed to play with a musket and tried to use a bow - quite successfully. It was a lot of fun.

Yours truly checking the firing mechanism of a musket.

My hair's a mess because of the wind.

Inside the great hall was a surgeon with his instruments, and more demonstrations like making butter and carding wool. No wonder I spent a lot of time in Caerphilly Castle.

Yes, I took pictures and I'll get the best ones up and running the next days.

The picture was again taken by Adrienne Goodeneough (Cadw) who some days later caught me in conversation with Master James in Caernarfon Castle.

but stiill pretty tired. Thank you all for the well wishes. That was one evil bug I caught there.

I have another fun pic for you. When I visited Caerphilly Castle, I came across a reenactment company demonstrating the use of muskets, archery and sword fighting. I managed to play with a musket and tried to use a bow - quite successfully. It was a lot of fun.

My hair's a mess because of the wind.

Inside the great hall was a surgeon with his instruments, and more demonstrations like making butter and carding wool. No wonder I spent a lot of time in Caerphilly Castle.

Yes, I took pictures and I'll get the best ones up and running the next days.

The picture was again taken by Adrienne Goodeneough (Cadw) who some days later caught me in conversation with Master James in Caernarfon Castle.

14 Aug 2008

The Regenstein: the Time of Heinrich the Lion

Since the early 11th century, the Regenstein and its fellow triad castles Blankenburg and Heimburg (see this post) served to protect the ways to the palatine castles and towns of Quedlinburg, Goslar and Magdeburg, but also the ways to the iron and silver mines of the Harz.

Guard tower, based on a natural sandstone formation

(I call it that, because the platform on top provides a fine view in all directions)

The Counts of Regenstein were partisans and probably vassals (the feudal rights are not entirely clear*) of Heinrich the Lion during his quarrels with the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa. Finally in 1180, the majority of the princes of the realm declared Heinrich, the most powerful rival among them, an outlaw. The emperor Friedrich Barbarossa distributed Heinrich's lands among some of the princes and then invaded Heinrich's Saxon possessions with an army to bring the rebel to task. Most of his allies abandoned Heinrich, and in 1181 he had to surrender at the diet of Erfurt and was condemned to exile.

* The Bishops of Halberstadt also claimed the overlordship.

One of the cliff promontories, seen from the curtain wall

The Count of Regenstein, either the aforementioned Konrad or his son, delivered the castle to Friedrich Barbarossa without resistance**, and was soon thereafter granted back the fief. In the following decades the family expanded the castle into a 100x175 square metres fortress with eight towers and about 200 metres curtain wall in addition to the natural cliffs. The St.Nicholas chapel dates from that time as well.

**An online source says the castle was destroyed, but I'm prone to believe the official guidebook, particularly since the fief seems to have been returned shortly after the surrender.

St.Nicholas Chapel, seen from the outside

(Added July 2015: This is another post in need of a rewirte. *sigh*)

Since the early 11th century, the Regenstein and its fellow triad castles Blankenburg and Heimburg (see this post) served to protect the ways to the palatine castles and towns of Quedlinburg, Goslar and Magdeburg, but also the ways to the iron and silver mines of the Harz.

(I call it that, because the platform on top provides a fine view in all directions)

The Counts of Regenstein were partisans and probably vassals (the feudal rights are not entirely clear*) of Heinrich the Lion during his quarrels with the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa. Finally in 1180, the majority of the princes of the realm declared Heinrich, the most powerful rival among them, an outlaw. The emperor Friedrich Barbarossa distributed Heinrich's lands among some of the princes and then invaded Heinrich's Saxon possessions with an army to bring the rebel to task. Most of his allies abandoned Heinrich, and in 1181 he had to surrender at the diet of Erfurt and was condemned to exile.

* The Bishops of Halberstadt also claimed the overlordship.

The Count of Regenstein, either the aforementioned Konrad or his son, delivered the castle to Friedrich Barbarossa without resistance**, and was soon thereafter granted back the fief. In the following decades the family expanded the castle into a 100x175 square metres fortress with eight towers and about 200 metres curtain wall in addition to the natural cliffs. The St.Nicholas chapel dates from that time as well.

**An online source says the castle was destroyed, but I'm prone to believe the official guidebook, particularly since the fief seems to have been returned shortly after the surrender.

(Added July 2015: This is another post in need of a rewirte. *sigh*)

9 Aug 2008

A Most Unusual Castle - The Regenstein

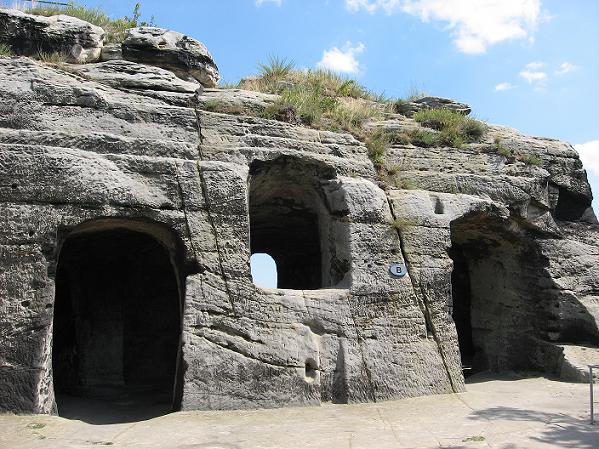

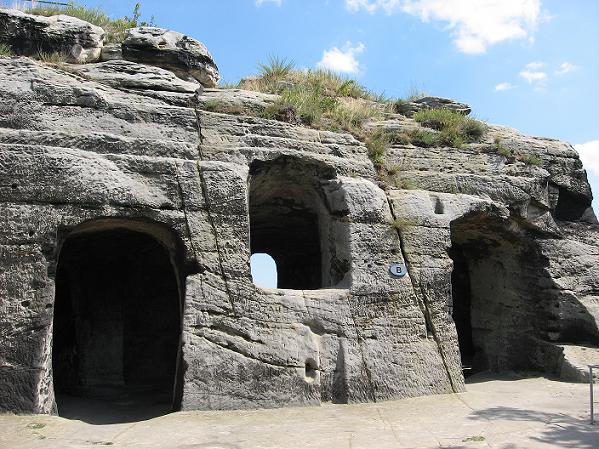

Wales may have the biggest castles, but we have the coolest. In particular the Regenstein is a very unusual construction. Situated on a 100 metres high sandstone cliff, it overlooks the plains northeast of the Harz mountains all the way to Quedlinburg and Halberstadt, and makes use of the natural caves in the rock. Most of them have been enlarged, and new ones have been added; for example one that was used as chapel in the 12th and 13th centuries and shows traces of an artificial cross grain vault ceiling hewn into the rock.

View towards the Regenstein with the keep and some of the caves

Archaeological traces show that the place has been used for several thousand years, probably as gathering spot for religious ceremonies. The Harz is full of those; a plateau on the Rosstrappe is another one - obviously such exposed cliffs have been regarded as places of power. The natural caves on the Regenstein (the name derives from rein - clear, white) may have been used as shelter of a hill fort.

Regenstein Castle, Keep

The first use as Mediaeval castle dates to the early 11th century, the time of the first Salian Emperor, Konrad II. A keep was built and fortifications added to the natural defenses. The Regenstein is not mentioned in Heinrich IV's wars against the Saxon nobles and may have escaped destruction. Later it came into the possession of the Harzgaugrafen (Harz Counts of the Mark) and was one of the castle triad of Regenstein, Blankenburg (today a Renaissance/Baroque palace) and Heimburg (only a few stones left). The most important of those was Lothar of Süpplingenburg whom we have met as founder of Königslutter Cathedral; the grandfather of Duke Henry the Lion.

Keep seen from the guard tower

When Lothar became Emperor in 1125, the Harz Mark County fell to vassals, and in 1169 one of them, another Konrad, appears as first Count of Regenstein. His brother held the Blankenburg. During his time the castle was enlarged and better fortified, a process that went on until about 1300. Since later times have used most of the stones (a good deal went into the Blankenburg Renaissance palace), what remains today is the ruins of the keep and some traces of the curtain walls and gates; most of the houses over the caves have disappeared.

Entrance to the north gate seen from inner bailey

In 1670, troops of the Prince Elector of Brandenburg occupied the Regenstein during a quarrel about feudal rights to the land, and developed the abandoned Medieaval castle into a mountain fortress with garrison buildings, bastions, stables and magazines etc. that would eventually encompass an area much larger than the old castle. Later the Regenstein came to Prussia but lost its strategical importance and was dismantled in 1758. Which in a way is lucky because the 'modern' buildings over the caves were deconstructed, thus giving the fortress back some of its look as Medieaval castle.

Guard house at the north gate

Since 1988 the place has undergone conservation and some restoration to preserve the ruins of the Medieaval castle and remains of the Baroque fortress, and specifically the intriguing mix of rock structures and architectural additions. It was fun to explore the place, a veritable labyrinth of stairs, caves, walkways and slopes. More about the Mediaeval history of the Regenstein will follow in another post (you didn't think I had only six or seven photos, did you? lol).

Wales may have the biggest castles, but we have the coolest. In particular the Regenstein is a very unusual construction. Situated on a 100 metres high sandstone cliff, it overlooks the plains northeast of the Harz mountains all the way to Quedlinburg and Halberstadt, and makes use of the natural caves in the rock. Most of them have been enlarged, and new ones have been added; for example one that was used as chapel in the 12th and 13th centuries and shows traces of an artificial cross grain vault ceiling hewn into the rock.

Archaeological traces show that the place has been used for several thousand years, probably as gathering spot for religious ceremonies. The Harz is full of those; a plateau on the Rosstrappe is another one - obviously such exposed cliffs have been regarded as places of power. The natural caves on the Regenstein (the name derives from rein - clear, white) may have been used as shelter of a hill fort.

The first use as Mediaeval castle dates to the early 11th century, the time of the first Salian Emperor, Konrad II. A keep was built and fortifications added to the natural defenses. The Regenstein is not mentioned in Heinrich IV's wars against the Saxon nobles and may have escaped destruction. Later it came into the possession of the Harzgaugrafen (Harz Counts of the Mark) and was one of the castle triad of Regenstein, Blankenburg (today a Renaissance/Baroque palace) and Heimburg (only a few stones left). The most important of those was Lothar of Süpplingenburg whom we have met as founder of Königslutter Cathedral; the grandfather of Duke Henry the Lion.

When Lothar became Emperor in 1125, the Harz Mark County fell to vassals, and in 1169 one of them, another Konrad, appears as first Count of Regenstein. His brother held the Blankenburg. During his time the castle was enlarged and better fortified, a process that went on until about 1300. Since later times have used most of the stones (a good deal went into the Blankenburg Renaissance palace), what remains today is the ruins of the keep and some traces of the curtain walls and gates; most of the houses over the caves have disappeared.

In 1670, troops of the Prince Elector of Brandenburg occupied the Regenstein during a quarrel about feudal rights to the land, and developed the abandoned Medieaval castle into a mountain fortress with garrison buildings, bastions, stables and magazines etc. that would eventually encompass an area much larger than the old castle. Later the Regenstein came to Prussia but lost its strategical importance and was dismantled in 1758. Which in a way is lucky because the 'modern' buildings over the caves were deconstructed, thus giving the fortress back some of its look as Medieaval castle.

Since 1988 the place has undergone conservation and some restoration to preserve the ruins of the Medieaval castle and remains of the Baroque fortress, and specifically the intriguing mix of rock structures and architectural additions. It was fun to explore the place, a veritable labyrinth of stairs, caves, walkways and slopes. More about the Mediaeval history of the Regenstein will follow in another post (you didn't think I had only six or seven photos, did you? lol).

23 Jul 2008

The Local Nobility and Their Castles - Adelebsen Keep

A rather unknown local castle just a few miles from Göttingen is Adelebsen. the only remaining Medieaval structure is the oddly shaped keep - Bergfried in German - the rest of the castle has been rebuilt into a Baroque palace. But the keep is quite impressive.

In 990, Emperor Otto III gave the land of Ethelleveshusen, situated on a military way (Heerstrasse), to his sister Sophie. Such places on the main roads were important at a time where the royal court still traveled around, and where troops often had to move at fast speed. The whole system culminated in the King's Highway (Königsweg or via regia) that runs all the way from the Rhine to the Baltic Sea and was king's land, no matter who possessed the fiefs along it, while the military ways tolled to the lord who held the land. He had to care for the upkeep in return. The King's Way still exists as hiking way.

A sandstone promontory rises above Adelebsen which is suited for a castle, and in 1234 the Lords of Wichbike moved from their old land that they held since at least 1111, to Adelebsen and built a castle there. They called themselves Lords of Adelebsen since 1295. Since the land belonged to the Emperor's sister, the fief likely was held directly from the king; a nice catch for a minor lord.

The oldest part of the castle is the keep, 38.75 metres high, pentangular in the lower part and six-sided in the upper part - it looks a bit twisted from certain angles. The walls are up to 4.30 metres thick and the main entrance 4 metres above ground. There had been 9 floors, but today the tower is empty inside with only a wooden staircase that leads to the roof running along the walls. But the keep is only open on special days so I haven't been inside yet. I don't really feel like climbing those open stairs, though the view of the surrounding landscape should be great.

The keep is one of the most impressive in Germany. The rest of the castle was mostly built in the 14th century as well but partly destroyed in 1466, during one of the many feuds between kings and nobles in Germany, and further during the Thirty Years War. In 1650, the castle was rebuilt in a more 'modern' style; and was changed into a Baroque palace in 1740; the trench between inner and outer bailey was then filled up. Several outbuildings were added, like a Hunter's Lodge and a Chamberlain's Office (Rentei, the yellow building in the first pic).

In 1947 the last Lord of Adelebsen gave part of his fortune to a foundation to ensure the castle, both the palace plus outbuildings and the Mediaeval keep, would remain in good condition. Yeah, it's not that much fun to inherit a drafty old tower with rotten floors even if it's been a family possession for 800 years. :)

A rather unknown local castle just a few miles from Göttingen is Adelebsen. the only remaining Medieaval structure is the oddly shaped keep - Bergfried in German - the rest of the castle has been rebuilt into a Baroque palace. But the keep is quite impressive.

In 990, Emperor Otto III gave the land of Ethelleveshusen, situated on a military way (Heerstrasse), to his sister Sophie. Such places on the main roads were important at a time where the royal court still traveled around, and where troops often had to move at fast speed. The whole system culminated in the King's Highway (Königsweg or via regia) that runs all the way from the Rhine to the Baltic Sea and was king's land, no matter who possessed the fiefs along it, while the military ways tolled to the lord who held the land. He had to care for the upkeep in return. The King's Way still exists as hiking way.

A sandstone promontory rises above Adelebsen which is suited for a castle, and in 1234 the Lords of Wichbike moved from their old land that they held since at least 1111, to Adelebsen and built a castle there. They called themselves Lords of Adelebsen since 1295. Since the land belonged to the Emperor's sister, the fief likely was held directly from the king; a nice catch for a minor lord.

The oldest part of the castle is the keep, 38.75 metres high, pentangular in the lower part and six-sided in the upper part - it looks a bit twisted from certain angles. The walls are up to 4.30 metres thick and the main entrance 4 metres above ground. There had been 9 floors, but today the tower is empty inside with only a wooden staircase that leads to the roof running along the walls. But the keep is only open on special days so I haven't been inside yet. I don't really feel like climbing those open stairs, though the view of the surrounding landscape should be great.

The keep is one of the most impressive in Germany. The rest of the castle was mostly built in the 14th century as well but partly destroyed in 1466, during one of the many feuds between kings and nobles in Germany, and further during the Thirty Years War. In 1650, the castle was rebuilt in a more 'modern' style; and was changed into a Baroque palace in 1740; the trench between inner and outer bailey was then filled up. Several outbuildings were added, like a Hunter's Lodge and a Chamberlain's Office (Rentei, the yellow building in the first pic).

In 1947 the last Lord of Adelebsen gave part of his fortune to a foundation to ensure the castle, both the palace plus outbuildings and the Mediaeval keep, would remain in good condition. Yeah, it's not that much fun to inherit a drafty old tower with rotten floors even if it's been a family possession for 800 years. :)

18 Jul 2008

Nessie of Loch Edersee

The lake looks peaceful on a warm summer afternoon. But the people in that sailing boat are not aware of the danger lurking in the cold, murky depths, seldom to surface. And if it does, beware!

If you look towards the bottom of the pic, in the wake of our boat you can see a fearsome monster rising its head. Or tail. Or whatever.

Behold, it is Nessie of Loch Edersee, the famous monster of Germany's largest reservoir lake, bane of boats and bathers alike. Sightings are rare, but for some reason she decided to follow our boat and allowed me to take some pictures.

Cute, isn't she? It's my niece's toy, and yes, she is called Nessie. The monster, not my niece. Her name is Mailin.

Here she is, giving Nessie some well deserved rest from racing through the cold water. The photo was taken last year; she's grown a bit since then.

The lake looks peaceful on a warm summer afternoon. But the people in that sailing boat are not aware of the danger lurking in the cold, murky depths, seldom to surface. And if it does, beware!

If you look towards the bottom of the pic, in the wake of our boat you can see a fearsome monster rising its head. Or tail. Or whatever.

Behold, it is Nessie of Loch Edersee, the famous monster of Germany's largest reservoir lake, bane of boats and bathers alike. Sightings are rare, but for some reason she decided to follow our boat and allowed me to take some pictures.

Cute, isn't she? It's my niece's toy, and yes, she is called Nessie. The monster, not my niece. Her name is Mailin.

Here she is, giving Nessie some well deserved rest from racing through the cold water. The photo was taken last year; she's grown a bit since then.

6 Jul 2008

Reconstructed Roman Walls

One of the features the Roman border fortresses share is the combination of a stone wall - surrounded by additional ditches and earthen walls - with an earthen rampart on the inside that also serves as battlement.

The reconstructed fortifications of the German Saalburg fortress present a good, if rain blurred, example.

You can see the outside of the walls here, and the ditches on the first picture in this post.

I suppose this unsual combination goes back to the history of Roman fortresses. They all began as semi-permanent structures with earthen walls and timber palisades on top, a more elaborate version of the marching camps.

Along the frontiers (the limes Germanicus, the Hadrian's Wall, the Syrian limes, and the Welsh forts) the fortresses were later rebuilt in stone, most of them in the 2nd century AD. Besides the stone buildings inside the forts, the defenses of earthen walls and trenches got an additional stone wall, watch towers, and stone gatehouses.

Cardiff castle shows another example of the reconstructed earth ramparts.

The outside of the wall can be seen on the first picture in this post. There are no trenches here today because of the situation in the middle of a town.

The Bute family made the reconstructed Roman fortifications into a park, thus the trees that would never have been allowed to grow there in times when a praefectus castrorum had the say.

The ramparts added to the stability of the walls, definitely well enough to stop a ram, and neither the German nor the British tribes had any more elaborate siege engines. They usually tried to climb the walls or breach the gates only to meet with pointy pila poking at them. Attacks on fortresses were not very frequent; the tribes prefered to attack the Romans outside when they were stretched out in marching columns.

One of the features the Roman border fortresses share is the combination of a stone wall - surrounded by additional ditches and earthen walls - with an earthen rampart on the inside that also serves as battlement.

The reconstructed fortifications of the German Saalburg fortress present a good, if rain blurred, example.

You can see the outside of the walls here, and the ditches on the first picture in this post.

I suppose this unsual combination goes back to the history of Roman fortresses. They all began as semi-permanent structures with earthen walls and timber palisades on top, a more elaborate version of the marching camps.

Along the frontiers (the limes Germanicus, the Hadrian's Wall, the Syrian limes, and the Welsh forts) the fortresses were later rebuilt in stone, most of them in the 2nd century AD. Besides the stone buildings inside the forts, the defenses of earthen walls and trenches got an additional stone wall, watch towers, and stone gatehouses.

Cardiff castle shows another example of the reconstructed earth ramparts.

The outside of the wall can be seen on the first picture in this post. There are no trenches here today because of the situation in the middle of a town.

The Bute family made the reconstructed Roman fortifications into a park, thus the trees that would never have been allowed to grow there in times when a praefectus castrorum had the say.

The ramparts added to the stability of the walls, definitely well enough to stop a ram, and neither the German nor the British tribes had any more elaborate siege engines. They usually tried to climb the walls or breach the gates only to meet with pointy pila poking at them. Attacks on fortresses were not very frequent; the tribes prefered to attack the Romans outside when they were stretched out in marching columns.

30 Jun 2008

A Castle for All Times - Cardiff

It began with the Romans who built a fort on the site of what is now Cardiff Castle, most probably during the campaign 55 AD against Caratacus (Caradog), a Catuvellauni chief who fled to the Silures in South Wales and sicced them against the Romans. They lost the war and Caratacus escaped to the Brigantes whose queen Cartimandua promptly delivered him to the Romans. He managed to talk his head ouf of getting chopped off (no wonder, he filched the speech from Tacitus) and ended his life in the sunny south, wearing a toga. The sources don't tell us if he missed the rain and his oatmeal porridge.

Remains of the Roman wall

visible at the bottom, framed by the red stones

The place near the Bristol channel was a strategically important position between the legionary fort at Caerleon and the fortress at Carmarthen. Cardiff - its Roman name is unknown - fortress encompassed ten acres and was, like all Roman forts, a timber and earth structure at first. During the war against Caratacus it probably held a legionary vexillatio, not an auxiliary cohort.

The fortress was rebuilt in 75 AD and again around 250 AD. This version had 10 feet thick stone walls backed by an earth fortification, and was in use until the Romans left Britain. The fortress seems to have served as naval base during that time.

After Constantine III dragged the army over to Gaul to tell the Emperor Honorius who was boss (didn't work, btw), the fortress fell into decline until 1091 when the Norman Robert Fitzhamon Lord of Gloucester, after having defetated the Welsh prince Iestyn ap Gwrgan of Glamorgan and claiming his lands, saw the remains and thought, hey, that looks like a good place for a castle, and there's even some of the walls left. So he planted one of those Norman motte and bailey thingies right in the middle of it.

The Norman Keep

Reminds of Clifford Tower, doesn't it?

The first version of the keep was of timber with a palisade, but the 40 feet high motte was surrounded by a moat filled with water. After Robert Fitzhamon died of wounds recieved in battle (remember Rob, the Welsh are never defeated), Cardiff Castle went to his son-in-law, another Robert 'the Consul', natural son of King Henry I, and one of the dominating characters during the struggle between Maud and Stephen.

He erected a stone keep, perhaps using some of the stones of the Roman buildings still lying around in what was to become the outer bailey. The spiffy new stone keep was then used to imprison another Robert (those Normans really needed a nameyourbébé.com site), Robert Duke of Normandy, from 1126 until his death in 1134.

After Robert's death (the other Robert, 'the Consul'), the castle changed hands several times. Among others, Cardiff Castle passed to Prince John Lackland for some years, thus proving he had at least ten acres of land at some point, and in 1216 the castle and the lordship of Glamorgan fell to Gilbert de Clare, one of the barons of the Magna Charta.

The de Clares needed all the castles they could get in South Wales, because the Welsh still thought the Normans sucked. Unfortunately, every Welsh prince thought his neighbours and his brothers sucked even worse, and so they failed to unite and kick the Normans out. Until Llywelyn ap Gruffydd first eliminated his brothers, solidified his rule over Gwynedd and then marched south to collect the allegiance of the Welsh nobles. In 1267, King Henry III had to acknowledge Llywelyn as Prince of Wales. But Llywelyn made the mistake to really piss off King Edward I and that didn't end well. In 1277, Edward showed him what a big bad Anglonorman army looked like by displaying his troops in full splendour at Chester, probably not knowing that big bad Roman armies had mustered there about thousand years earlier. Llywelyn had to sue for peace and lost his title and most of his possessions. He died in a skirmish later that year.

Norman Keep, inside

The lands of Glamorgan and Cardiff as administrative seat lay in a sensitive spot during these quarrels, and so Gilbert de Clare's grandson, another Gilbert, remodeled the keep and further strengthened the castle by dividing the terrain of the ancient Roman fortress by a wall, thus creating an inner and outer bailey, and reinforcing the Roman fortifications as outer curtain walls. He also built Caerphilly Castle.

Gilbert's son, Gilbert the younger (you guessed that, didn't you?) died at Bannockburn in 1314. The lordship passed to his sister Eleanor who had married Hugh Despenser; that family would retain the lordship of Glamorgan for a hundred years. I will get back to our (in)famous Despensers in another post - Lady D and Kathryn would hang, draw and quarter me if I reduced their darling Despensers to a footnote. :) Suffice to say that the lordship passed to the Beauchamp earls of Warwick in 1414 and finally into the hands of the Tudor kings.

In 1550 William Herbert, brother of Catherine Parr, Henry VIII's last wife, obtained Cardiff Castle which fortunately wasn't destroyed during the Civil War and remained with the family until 1766 when Cardiff Castle and the Glamorgan lands came into the hands of John Stuart Earl of Bute by marriage to Charlotte Herbert. The Bute family fully embraced industrialization and could have given Bill Gates and that Trump guy a run for their money; they were among the richest families in the word, and Cardiff became a major export port.

The Neo Gothic part of the castle

They also took interest in the Roman past of Cardiff Castle (which was a good thing) and transformed the castle into a Neo Gothic dream palace (which at least makes for a grin these days). In 1865, Lord Bute began a partnership with the architect William Burges with the result that we now have a really fancy thing with lots of turrets, spires, oriels, fake merlons, and rooms with the most splendid, but un-Mediaeval furniture, tapestries and whatever. Fortunately, the Butes decided not to alter the Norman Keep, and the reconstructions of the Roman walls and the North Gate are a commendable effort to preserve and reconstruct the past. The German Emperor Wilhelm did the same with the Saalburg Roman fortress.

Reconstructed Roman North Gate

As with the Saalburg, the walls are not whitewashed

Reconstruction and reimagination work on all parts of the castle was going on basically from 1770 to 1927. Thus the castle is a mix of Norman, reinvented Norman (oh yes, we have a Bute Tower, a Herbert Tower, a Guest Tower ...) Mediaeval, reinvented Mediaeval (there's a Mediaeval Great Hall? fun, let's have our own Banqueting Hall besides), Tudor, reinvented Tudor (the roof of the Octagon Tower looks prettier with a fancy spire), and reconstructed Roman architecture.

Cardiff Castle escaped enemy action during WW2, but Labour governments don't like people getting too rich and invented heritage taxes. In 1947, the 5th Marquess of Bute gave Cardiff Castle to the people because the upkeep was too expensive.

It began with the Romans who built a fort on the site of what is now Cardiff Castle, most probably during the campaign 55 AD against Caratacus (Caradog), a Catuvellauni chief who fled to the Silures in South Wales and sicced them against the Romans. They lost the war and Caratacus escaped to the Brigantes whose queen Cartimandua promptly delivered him to the Romans. He managed to talk his head ouf of getting chopped off (no wonder, he filched the speech from Tacitus) and ended his life in the sunny south, wearing a toga. The sources don't tell us if he missed the rain and his oatmeal porridge.

visible at the bottom, framed by the red stones

The place near the Bristol channel was a strategically important position between the legionary fort at Caerleon and the fortress at Carmarthen. Cardiff - its Roman name is unknown - fortress encompassed ten acres and was, like all Roman forts, a timber and earth structure at first. During the war against Caratacus it probably held a legionary vexillatio, not an auxiliary cohort.

The fortress was rebuilt in 75 AD and again around 250 AD. This version had 10 feet thick stone walls backed by an earth fortification, and was in use until the Romans left Britain. The fortress seems to have served as naval base during that time.

After Constantine III dragged the army over to Gaul to tell the Emperor Honorius who was boss (didn't work, btw), the fortress fell into decline until 1091 when the Norman Robert Fitzhamon Lord of Gloucester, after having defetated the Welsh prince Iestyn ap Gwrgan of Glamorgan and claiming his lands, saw the remains and thought, hey, that looks like a good place for a castle, and there's even some of the walls left. So he planted one of those Norman motte and bailey thingies right in the middle of it.

Reminds of Clifford Tower, doesn't it?

The first version of the keep was of timber with a palisade, but the 40 feet high motte was surrounded by a moat filled with water. After Robert Fitzhamon died of wounds recieved in battle (remember Rob, the Welsh are never defeated), Cardiff Castle went to his son-in-law, another Robert 'the Consul', natural son of King Henry I, and one of the dominating characters during the struggle between Maud and Stephen.

He erected a stone keep, perhaps using some of the stones of the Roman buildings still lying around in what was to become the outer bailey. The spiffy new stone keep was then used to imprison another Robert (those Normans really needed a nameyourbébé.com site), Robert Duke of Normandy, from 1126 until his death in 1134.

After Robert's death (the other Robert, 'the Consul'), the castle changed hands several times. Among others, Cardiff Castle passed to Prince John Lackland for some years, thus proving he had at least ten acres of land at some point, and in 1216 the castle and the lordship of Glamorgan fell to Gilbert de Clare, one of the barons of the Magna Charta.

The de Clares needed all the castles they could get in South Wales, because the Welsh still thought the Normans sucked. Unfortunately, every Welsh prince thought his neighbours and his brothers sucked even worse, and so they failed to unite and kick the Normans out. Until Llywelyn ap Gruffydd first eliminated his brothers, solidified his rule over Gwynedd and then marched south to collect the allegiance of the Welsh nobles. In 1267, King Henry III had to acknowledge Llywelyn as Prince of Wales. But Llywelyn made the mistake to really piss off King Edward I and that didn't end well. In 1277, Edward showed him what a big bad Anglonorman army looked like by displaying his troops in full splendour at Chester, probably not knowing that big bad Roman armies had mustered there about thousand years earlier. Llywelyn had to sue for peace and lost his title and most of his possessions. He died in a skirmish later that year.

The lands of Glamorgan and Cardiff as administrative seat lay in a sensitive spot during these quarrels, and so Gilbert de Clare's grandson, another Gilbert, remodeled the keep and further strengthened the castle by dividing the terrain of the ancient Roman fortress by a wall, thus creating an inner and outer bailey, and reinforcing the Roman fortifications as outer curtain walls. He also built Caerphilly Castle.

Gilbert's son, Gilbert the younger (you guessed that, didn't you?) died at Bannockburn in 1314. The lordship passed to his sister Eleanor who had married Hugh Despenser; that family would retain the lordship of Glamorgan for a hundred years. I will get back to our (in)famous Despensers in another post - Lady D and Kathryn would hang, draw and quarter me if I reduced their darling Despensers to a footnote. :) Suffice to say that the lordship passed to the Beauchamp earls of Warwick in 1414 and finally into the hands of the Tudor kings.

In 1550 William Herbert, brother of Catherine Parr, Henry VIII's last wife, obtained Cardiff Castle which fortunately wasn't destroyed during the Civil War and remained with the family until 1766 when Cardiff Castle and the Glamorgan lands came into the hands of John Stuart Earl of Bute by marriage to Charlotte Herbert. The Bute family fully embraced industrialization and could have given Bill Gates and that Trump guy a run for their money; they were among the richest families in the word, and Cardiff became a major export port.

They also took interest in the Roman past of Cardiff Castle (which was a good thing) and transformed the castle into a Neo Gothic dream palace (which at least makes for a grin these days). In 1865, Lord Bute began a partnership with the architect William Burges with the result that we now have a really fancy thing with lots of turrets, spires, oriels, fake merlons, and rooms with the most splendid, but un-Mediaeval furniture, tapestries and whatever. Fortunately, the Butes decided not to alter the Norman Keep, and the reconstructions of the Roman walls and the North Gate are a commendable effort to preserve and reconstruct the past. The German Emperor Wilhelm did the same with the Saalburg Roman fortress.

As with the Saalburg, the walls are not whitewashed

Reconstruction and reimagination work on all parts of the castle was going on basically from 1770 to 1927. Thus the castle is a mix of Norman, reinvented Norman (oh yes, we have a Bute Tower, a Herbert Tower, a Guest Tower ...) Mediaeval, reinvented Mediaeval (there's a Mediaeval Great Hall? fun, let's have our own Banqueting Hall besides), Tudor, reinvented Tudor (the roof of the Octagon Tower looks prettier with a fancy spire), and reconstructed Roman architecture.

Cardiff Castle escaped enemy action during WW2, but Labour governments don't like people getting too rich and invented heritage taxes. In 1947, the 5th Marquess of Bute gave Cardiff Castle to the people because the upkeep was too expensive.

24 Jun 2008

Dungeons (No Dragons)

A typical Mediaeval castle needs a typical dungeon, dark, wet, full of rats, shackles dangling from the walls, and maybe even equipped with a rack. All the medieaval-based Fantasy novels have them, after all. *grin*

There are indeed dungeons in some Welsh castles, or rooms that could be used as such. Though noble prisoners kept for ransom were not held under such unfavourable conditions. But when captivity was intended as punishment, even a title may not have saved you from moldy straw and rats.

Pembroke Castle has a very fine example of a gaol built into a tower, with only one small slit in the eastern wall to let a glimpse of light in. The oubliette can only be reached through a trap door in the floor of the upper room, and it's the only angle to get a pic as well.

If you look closely, you can see a little rat. It's dinner time. :)

Somewhat larger but no more comfortable is the dungeon in Manorbier Castle. If you end up with your legs in the stocks and hands tied behind your back, you'll be in for all sort of aches and your back will not love you. Don't think it was so well lit; I had to use a flash or you'd not have seen anything.

German castles have dungeons, too, and some are catered to the tourists by suitable decorations as well. No wax figures this time, but a nice rack - albeit someone should do something about the un-scary dust layer - and some shackles.

This fun display is in the Hanstein Castle, mentioned several times on my blog. Though we don't know if there was indeed not only a dungeon but a torture chamber as well. The sources don't mention one, as far as I know. Not that one needs a lot of sophisticated equipment to torture a prisoner.

A typical Mediaeval castle needs a typical dungeon, dark, wet, full of rats, shackles dangling from the walls, and maybe even equipped with a rack. All the medieaval-based Fantasy novels have them, after all. *grin*

There are indeed dungeons in some Welsh castles, or rooms that could be used as such. Though noble prisoners kept for ransom were not held under such unfavourable conditions. But when captivity was intended as punishment, even a title may not have saved you from moldy straw and rats.

Pembroke Castle has a very fine example of a gaol built into a tower, with only one small slit in the eastern wall to let a glimpse of light in. The oubliette can only be reached through a trap door in the floor of the upper room, and it's the only angle to get a pic as well.

If you look closely, you can see a little rat. It's dinner time. :)

Somewhat larger but no more comfortable is the dungeon in Manorbier Castle. If you end up with your legs in the stocks and hands tied behind your back, you'll be in for all sort of aches and your back will not love you. Don't think it was so well lit; I had to use a flash or you'd not have seen anything.

German castles have dungeons, too, and some are catered to the tourists by suitable decorations as well. No wax figures this time, but a nice rack - albeit someone should do something about the un-scary dust layer - and some shackles.

This fun display is in the Hanstein Castle, mentioned several times on my blog. Though we don't know if there was indeed not only a dungeon but a torture chamber as well. The sources don't mention one, as far as I know. Not that one needs a lot of sophisticated equipment to torture a prisoner.

22 Jun 2008

Lost Kingdoms and Sunken Realms

I found some Welsh legends of sunken kingdoms. Considering the fact the country has a long stretch of coast with heavy tides, it should not come as suprise that such legends arose as result of floods. Moreover, the Welsh share a Celtic culture with the Bretons where such a legend is famous as well, that of Kêr Ys (Kêr/Caer, meaning fortress or stronghold).

Cantre'r Gwaelod is a legendary kingdom said to have occupied a tract of fertile land northwest of Aberystwyth, todays Cardigan Bay. Its capital was Caer Wyddno, seat of the ruler Gwyddno Garanhir, who in some legends is connected with Taliesin as grandfather or foster father.

Like Kêr Ys, the kingdom was protected from the sea by floodgates. One day the keeper of the sluice gates was drunk and failed to close them, with the result that the sea flooded the land. Some versions name the keeper as Seithenyn, and there is a story about him having been distracted by a woman, Mererid, who kept the keys to the sluices. Or maybe it was a fae responsible for the mess.

Gwyddno also held a landlocked portion of his kingdom to which he was able to flee, like King Gradlon of Kêr Ys. He was later called King of Ceredigion. The church bells of Cantre'r Gwaelod are said to ring out in times of danger, a legend shared with Vineta, a sunken city in the Baltic Sea.

The coast of Aberystwyth

Llys Helig was the palace of Prince Helig ap Glannawg who is said to have lived in the 6th century, and whose sons are connected with the establishment of several churches in the area. Helig owned an area of land between Llandudno and Conwy which was later inundated by the sea. Like Vineta's shadows in clear water, it is said that the remains of Llys Helig can be seen at low tides,

Some versions of the legend tell that the flood was the result of revenge because Helig's daughter Gwendud was unfaithful in love. In another version her lover Tathal treacherously murdered a Scottish chieftain to gain a gold torque and her hand, and the victim swore vengeance.

I found some Welsh legends of sunken kingdoms. Considering the fact the country has a long stretch of coast with heavy tides, it should not come as suprise that such legends arose as result of floods. Moreover, the Welsh share a Celtic culture with the Bretons where such a legend is famous as well, that of Kêr Ys (Kêr/Caer, meaning fortress or stronghold).

Cantre'r Gwaelod is a legendary kingdom said to have occupied a tract of fertile land northwest of Aberystwyth, todays Cardigan Bay. Its capital was Caer Wyddno, seat of the ruler Gwyddno Garanhir, who in some legends is connected with Taliesin as grandfather or foster father.

Like Kêr Ys, the kingdom was protected from the sea by floodgates. One day the keeper of the sluice gates was drunk and failed to close them, with the result that the sea flooded the land. Some versions name the keeper as Seithenyn, and there is a story about him having been distracted by a woman, Mererid, who kept the keys to the sluices. Or maybe it was a fae responsible for the mess.

Gwyddno also held a landlocked portion of his kingdom to which he was able to flee, like King Gradlon of Kêr Ys. He was later called King of Ceredigion. The church bells of Cantre'r Gwaelod are said to ring out in times of danger, a legend shared with Vineta, a sunken city in the Baltic Sea.

Llys Helig was the palace of Prince Helig ap Glannawg who is said to have lived in the 6th century, and whose sons are connected with the establishment of several churches in the area. Helig owned an area of land between Llandudno and Conwy which was later inundated by the sea. Like Vineta's shadows in clear water, it is said that the remains of Llys Helig can be seen at low tides,

Some versions of the legend tell that the flood was the result of revenge because Helig's daughter Gwendud was unfaithful in love. In another version her lover Tathal treacherously murdered a Scottish chieftain to gain a gold torque and her hand, and the victim swore vengeance.

9 Jun 2008

Master James of St.George

No, Gabriele didn't make me up like she did with that Aelius Rufus guy, I'm a real person who lived from 1235-1308. And sometimes I return to my old places like Caernarfon Castle and talk to people.

Here I'm deep in conversation with Gabriele about the payment of masons*. I know a lot about that matter because I've been a master mason and military engineer all my life, following the footsteps of my father.

Here I'm deep in conversation with Gabriele about the payment of masons*. I know a lot about that matter because I've been a master mason and military engineer all my life, following the footsteps of my father.

First I worked for the Counts of Savoy, and I took my name after the palace of St. Georges d'Esperanche which I built for Philip of Savoy. In 1278, Count Philip was visited by King Edward I of England who had a problem. He had conquered a people called the Welsh, but they took ill having a king not of their own blood and made several attempts to oust Edward. Thus he planned to build a ring of castles around the land to strengthen the position of the English. I wasn't sure at first if I really wanted to work in a land full of mountains, wind, rain and savage people who spoke an incomprehensible language with far too many ll and dd, but the payment was excellent and Edward ensured me he wanted the biggest fortresses he could get. It should prove an interesting challenge and so I packed my belongings, picked the best masons and engineers from my staff, received the farewell of Count Philip and set off to Wales.

It was a challenge, even with sixteen years of experience in building castles. Over the years I oversaw the construction of the castles of Caernarfon, Conwy, Harlech, Beaumaris, Flint, Rhuddlan, Builth and Aberystwyth, and I was involved in the repair and refortification of Dolwyddelan and Criccieth, Welsh castles which Edward had conquered.

Caernarfon Castle, view towards Eagle Tower

But my favourite place is Caernarfon which I modeled after the walls of Constantinople. For some reason, the Romans still hold a popular place in Welsh myths despite the fact they came as conquerors as well, and so Edward got the idea to connect his reign to the Roman Emperor Maximus, whom the Welsh call Macsen Wledig, and he wanted to demonstrate this by building a Roman-style castle. The Romans had been in Caernarfon which they called Segontium; you can visit the remains of their fortress on yonder hill. They produced some fine stone work, those Romans.

As you can see, Caernarfon has octagonal towers instead of round ones, and we used two different sorts of stone to create the red stripes. I'll tell you more about constructing a castle next time, it's a long and complicated process, and the walls and towers you see today only the final result. There are also some features I would have liked to add but never got the chance. Edward wanted too many castles at once, and in the end there was not enough money left.

View towards Queen's Gate

It was not my fault. Yes, I did receive the handsome pay of two shilling a day which was later raised to three shilling a day for the rest of my life, but that doesn't account for the 12,000 pound the building of Caernarfon cost from 1283-1292. You wonder what three shilling were actually worth? Well, I made in one day what a skilled mason who was not a chief engineer and Master would make in a week. A simple labourer digging trenches and such made two pennies a day, and one penny would buy him food and wine and a bed at an inn. If he spent the other penny on a whore, he'd be in for some trouble with his wife, though.

The comparably low payment for digging trenches should explain some of Edward I's annoyance with his son's hobbies, Ed II could never have made a living off those. *grin*

* The above picture was taken by Adrienne Goodenough from Cadw. She organises educational events in historical sites managed by Cadw and was so kind to send me the pictures she took of me and Master James. I hope the actor who played him - I never learned his real name - won't mind that I use James as narrator for some of my blogposts, but he was fun and an inspiration. The information about payment I got from him, but the rest is based on the info in the guidebook.

No, Gabriele didn't make me up like she did with that Aelius Rufus guy, I'm a real person who lived from 1235-1308. And sometimes I return to my old places like Caernarfon Castle and talk to people.

Here I'm deep in conversation with Gabriele about the payment of masons*. I know a lot about that matter because I've been a master mason and military engineer all my life, following the footsteps of my father.

Here I'm deep in conversation with Gabriele about the payment of masons*. I know a lot about that matter because I've been a master mason and military engineer all my life, following the footsteps of my father. First I worked for the Counts of Savoy, and I took my name after the palace of St. Georges d'Esperanche which I built for Philip of Savoy. In 1278, Count Philip was visited by King Edward I of England who had a problem. He had conquered a people called the Welsh, but they took ill having a king not of their own blood and made several attempts to oust Edward. Thus he planned to build a ring of castles around the land to strengthen the position of the English. I wasn't sure at first if I really wanted to work in a land full of mountains, wind, rain and savage people who spoke an incomprehensible language with far too many ll and dd, but the payment was excellent and Edward ensured me he wanted the biggest fortresses he could get. It should prove an interesting challenge and so I packed my belongings, picked the best masons and engineers from my staff, received the farewell of Count Philip and set off to Wales.

It was a challenge, even with sixteen years of experience in building castles. Over the years I oversaw the construction of the castles of Caernarfon, Conwy, Harlech, Beaumaris, Flint, Rhuddlan, Builth and Aberystwyth, and I was involved in the repair and refortification of Dolwyddelan and Criccieth, Welsh castles which Edward had conquered.

But my favourite place is Caernarfon which I modeled after the walls of Constantinople. For some reason, the Romans still hold a popular place in Welsh myths despite the fact they came as conquerors as well, and so Edward got the idea to connect his reign to the Roman Emperor Maximus, whom the Welsh call Macsen Wledig, and he wanted to demonstrate this by building a Roman-style castle. The Romans had been in Caernarfon which they called Segontium; you can visit the remains of their fortress on yonder hill. They produced some fine stone work, those Romans.

As you can see, Caernarfon has octagonal towers instead of round ones, and we used two different sorts of stone to create the red stripes. I'll tell you more about constructing a castle next time, it's a long and complicated process, and the walls and towers you see today only the final result. There are also some features I would have liked to add but never got the chance. Edward wanted too many castles at once, and in the end there was not enough money left.

It was not my fault. Yes, I did receive the handsome pay of two shilling a day which was later raised to three shilling a day for the rest of my life, but that doesn't account for the 12,000 pound the building of Caernarfon cost from 1283-1292. You wonder what three shilling were actually worth? Well, I made in one day what a skilled mason who was not a chief engineer and Master would make in a week. A simple labourer digging trenches and such made two pennies a day, and one penny would buy him food and wine and a bed at an inn. If he spent the other penny on a whore, he'd be in for some trouble with his wife, though.

The comparably low payment for digging trenches should explain some of Edward I's annoyance with his son's hobbies, Ed II could never have made a living off those. *grin*

* The above picture was taken by Adrienne Goodenough from Cadw. She organises educational events in historical sites managed by Cadw and was so kind to send me the pictures she took of me and Master James. I hope the actor who played him - I never learned his real name - won't mind that I use James as narrator for some of my blogposts, but he was fun and an inspiration. The information about payment I got from him, but the rest is based on the info in the guidebook.

1 Jun 2008

The Pleasantest Spot in Wales

Thus described Gerald of Wales (1146-1223) his birthplace Manorbier Castle at the coast of south Wales. I won't give it this title alone of all places I've seen, but it is surely among the prettiest sites. And since I caught a sunny day for my visit, Manorbier showed itself to advantage.

Manorbier Castle

12th century Giraldus Cambrensis must have been quite a character, churchman, writer, traveler, diplomat, and a spy and outlaw at a time. But we can thank him for a fine description of Medieaval Wales. His grandfather, a Norman lord of the de Barri family, was granted the lands of Manorbier some time after 1003 and built a timber castle that was expanded in stone by his son William, Gerald's father. The castle remained in possession of the family until 1359 when it fell back to the crown.

William married a daughter of the famous Nest of Deheubarth daughter of Prince Rhys ap Tewdwr, which made Gerald a descendant of two noble houses, Norman and Welsh.

Manorbier Castle, inner ward

Manorbier, though well fortified, presents a less grand impression than fe. Pembroke or Caernarfon. It reminded me more of the German castles around my hometown albeit it keeps its specific Norman features that distinguish it from our hill castles. It is more the size and the fact it has become some sort of park. The other Norman castles only have lawns in the wards but no trees and flowers which of course, adds to the enormous scale of the places, while the German castles display trees in the yards and bushes in the bailey. You may remember the foliage on my photos from the Hanstein and Plesse. The inner ward of Manorbier tops them with its abundance of flowers and greens growing in beds along the walls.

Manorbier Castle, inner ward

Another feature Manorbier has in common with 'my' castles is the hall-keep that is built directly into the inner curtain wall, like this example (second photo) from the Hanstein shows, instead of a freestanding structure typical for Norman castles. In the 1260ies a chapel was added to the inner buildings which is preserved until today, as well as the vaulted basement under the entire hall block.

In former times, Manorbier was closer to the sea that still can be seen from the windows, and had a sea gate. But the changes in geography have added a fine beach today.

Beach near Manorbier Castle

I spent some time down there, walked through the breakers playing on the sand and enveloping the rocks with foam, sat in the warm sand and felt like during my childhood holidays at the Baltic Sea. Including the sand I kept finding in my clothes the rest of the day. Memories indeed, lol. I could not resist to bring some pretty stones and mussles, either.

A pleasant spot indeed, and a fine day to remember.

Thus described Gerald of Wales (1146-1223) his birthplace Manorbier Castle at the coast of south Wales. I won't give it this title alone of all places I've seen, but it is surely among the prettiest sites. And since I caught a sunny day for my visit, Manorbier showed itself to advantage.

12th century Giraldus Cambrensis must have been quite a character, churchman, writer, traveler, diplomat, and a spy and outlaw at a time. But we can thank him for a fine description of Medieaval Wales. His grandfather, a Norman lord of the de Barri family, was granted the lands of Manorbier some time after 1003 and built a timber castle that was expanded in stone by his son William, Gerald's father. The castle remained in possession of the family until 1359 when it fell back to the crown.

William married a daughter of the famous Nest of Deheubarth daughter of Prince Rhys ap Tewdwr, which made Gerald a descendant of two noble houses, Norman and Welsh.

Manorbier, though well fortified, presents a less grand impression than fe. Pembroke or Caernarfon. It reminded me more of the German castles around my hometown albeit it keeps its specific Norman features that distinguish it from our hill castles. It is more the size and the fact it has become some sort of park. The other Norman castles only have lawns in the wards but no trees and flowers which of course, adds to the enormous scale of the places, while the German castles display trees in the yards and bushes in the bailey. You may remember the foliage on my photos from the Hanstein and Plesse. The inner ward of Manorbier tops them with its abundance of flowers and greens growing in beds along the walls.

Another feature Manorbier has in common with 'my' castles is the hall-keep that is built directly into the inner curtain wall, like this example (second photo) from the Hanstein shows, instead of a freestanding structure typical for Norman castles. In the 1260ies a chapel was added to the inner buildings which is preserved until today, as well as the vaulted basement under the entire hall block.

In former times, Manorbier was closer to the sea that still can be seen from the windows, and had a sea gate. But the changes in geography have added a fine beach today.

I spent some time down there, walked through the breakers playing on the sand and enveloping the rocks with foam, sat in the warm sand and felt like during my childhood holidays at the Baltic Sea. Including the sand I kept finding in my clothes the rest of the day. Memories indeed, lol. I could not resist to bring some pretty stones and mussles, either.

A pleasant spot indeed, and a fine day to remember.